Wanna see something gross?

Not really, no.

Don’t care, bolded alter-ego. Feast your eyes on this:

What.

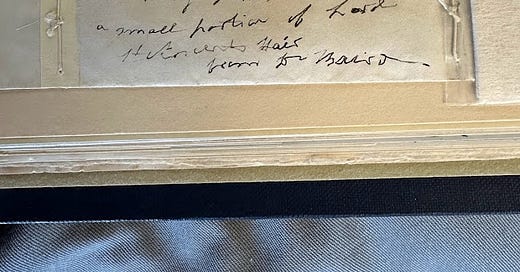

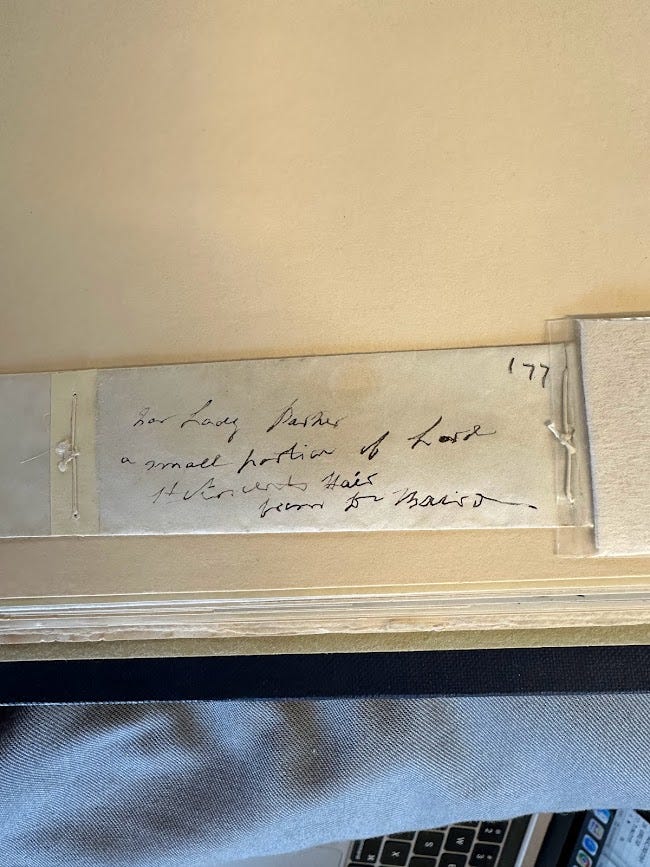

If you need help with the nineteenth-century handwriting, it says: “For Lady Parker, a small portion of Lord St. Vincent’s Hair, from Dr. Baird.”

Yep, that’s hair! 201-year-old hair!

Nope.

I can verify that the packet does actually contain hair. Like, I could feel it in there, all dry and spindly. It also explains why the handwriting is a little jankier than usual—the pen kept slipping on the bundle of hair inside the envelope.

… but why were you feeling old hair.

Unfortunately (fortunately?), I wasn’t able to open it to look at the actual hair because the person monitoring the reading room told me that the conservation department would have to get involved to undo those tiny knots. There’s also a seal on the right-hand side, which was broken, but the ties kept the whole thing shut. It’s probably for the best that I couldn’t get it out, but I was a little disappointed (relieved?).

Well, I’m definitely relieved. But I didn’t mean, why didn’t you take it out of the envelope. I meant, why were you interacting with this hair in the first place?

Because of the characters involved! The main character—the man who grew the hair—is John Jervis, first earl of St. Vincent (1735–1823). He was, among other things, Admiral of the Fleet and First Lord of the Admiralty. The former meant he was the highest-ranking naval officer in Britain; the latter meant he was the cabinet member responsible for the navy. He’s best-known today as Nelson’s patron and as the victor of the Battle of Cape St. Vincent in 1797, from which he got the name of his earldom.

I haven’t figured out yet exactly which Lady Parker this was, but St. Vincent was related by both marriage and parentage to the Parkers. He married his first cousin, Martha Parker, but they did not have any children (which is probably for the best, genetically speaking). He outlived his cousin-wife, and pretty much everyone else from his generation, so my best guess is that this Lady Parker was his niece or grand-niece.

Dr. Andrew Baird was St. Vincent’s personal physician, and since St. Vincent held many powerful positions in the navy, he was able to appoint Baird to a variety of posts in naval medicine. The implication of the hair sample is that Baird snipped the hair from St. Vincent’s dead head immediately after St. Vincent died.

Please tell my doctors not to do that to me.

Will do.

But, like, why? Why is there hair there?

I’m not an expert on why someone would do this, but it was a pretty common practice. It’s not the first time I’ve found hair in an archive, and I suspect it won’t be the last. In many cases, the hair would be kept in a locket or some other kind of keepsake, as a way of maintaining a connection to the deceased. It’s hard for me to tell whether Lady Parker did that in this case. It appears in the archival record immediately after an envelope with a similar description on it, which enclosed the packet you see in the photo above, but I don’t think it was the envelope that Baird used to send the hair. So Lady Parker may have had the hair for a while, presumably in a better container, before donating it to the collection that ended up in the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich.

OK, but why were you looking at this old hair specifically?

I’m writing a biography of St. Vincent, so I’m interested in pretty much everything about him, from birth to death. I didn’t think I was going to be interested in his hair, but here we are. I was surprisingly moved by it, I have to admit. It’s by far the closest I’m ever going to get to his person, the rest of which is in the little village of Stone in Staffordshire.

I’m spending years of my life thinking about this man’s life, and the primary way that I learn about his life is to read his surviving letters. I’ve read thousands already, and I have thousands more to read. The letters allow me to recognize his handwriting at a glance, sketch out the major components of his personality, and situate him in his professional and personal networks.

But there are always unknowns. Many documents don’t survive (his flagship exploded in 1795, for example) and the rest are subject to the usual problems of interpretation and context. For some questions—too often, the most important ones—the only person who could answer them would be the man himself. Obviously that’s not possible, but it was jarring to flip page after page of letters in the usual way, only to be confronted with a little piece of him. That was unusual.

And also kinda gross.

Yes.

I worked as a postgraduate 'intern' at the US Navy Archives here in Washington DC for 6 months and while my access was limited to specific materials related to work assignments I did get to process a late Rear Admiral's photos and memorabilia from the Antarctic expeditions between World War 1 and 2! The only thing I find even more exciting is getting access to the stacks where they keep ALL the books - something apparently almost no one allows any more after numerous sad experiences.