Master and Commander - Chapter Two

From shore to ship

The ten scenes of Chapter Two serve as a long bridge from land to ship. It risks boredom.

Jack and Stephen begin by dining “in an inn high above the water … [above] the mingled scents of Stockholm tar, cordage, sail-cloth and Chian turpentine.” The chapter ends with the Sophie making sail, with Jack in his first command and Stephen as the ship’s surgeon and a very large sea drama set to begin, with prize sails on the horizons, as well as the frigate Cacafuego, tool of Spanish revenge and the novel’s ultimate conflict. In time the drama will return to land, where sailors lose their balance. And yet our heroes will meet Sophia Williams and Diana Villiers.

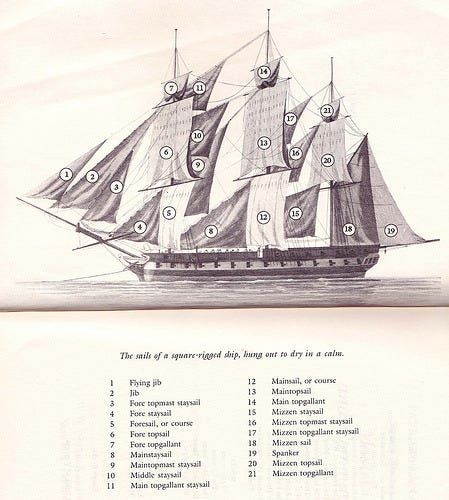

A historical novelist must create a reality true to the time. The task demands accurate detail. In these forty-nine pages we learn how the ship is outfitted, who the crew is, how the command is supposed to work. The unfamiliar details of the outfitting can overwhelm—double thin-coaks, clew-garnets, cro’jacks, cross-catharpings, ratlines, after-cockpits, and sails from the flying jib to the spanker. From the shipyard Mr. Brown speaks of spars, hawsers, stoppers, spun yarn, and hawse. Perhaps Ralph Fiennes could read the ship’s logbook in dramatic fashion, but it’s two dull pages long. The front matter’s illustration helps—twenty-one sails on a square-rigged ship are pictured and labeled—but a single illustration is not going to solve the challenges O’Brian faces to keep the reader’s attention (particularly the landlubber’s). And, if outfitting and sails are not enough to confuse, O’Brian does not limit his details to the King’s ship. There is Stephen Maturin’s phanerograms, hook-throned caper bushs, hypnoguges, the correct Cataline word senglar (and not the Spanish jabali), trocars, ball-scoops, saws, and bone-rasps. This fullness of detail convinces, without doubt (this writer knows what he’s writing about!), but it also can slow and even block the human drama.

And yet our enthusiast, Jack Aubrey, despises a dull life and a command that isn’t shipshape. His efforts to prepare the ship give us an expectation—the Sophie is going to sail—but then the problems and repeated confrontations block fulfilling our expectation. Jack has corruption to deal with and catches out the purser’s financial deceits. He barks at a new sailor for disrespect before he’s told the man’s tongue was cut out. When carpenters kneel before him to object to his cannonades, he curses them. With an “unaffected blaze of indignation” that makes him “red in the face,” he comes onto a deck “not unlike Cheapside with roadwork going on” and admonishes a warrant officer: “By the time I come back [from ashore], this deck will present a very different appearance.” He kicks the women off the ship, argues with Mr. Lamb, demands silence when the mast is fitted. This dramatic stirring up, this push against the expectation to sail, makes each of the ten scenes only inch toward a sailing the way the enthusiast wants and the way the reader needs—our expectation must be resolved, soon preferably, at least in some manner. Eventually he will brandish a hierarchical command to sail the ship and demand its men risk their very lives not simply to sail through wind and storm and unexpected drops into the sea but pursue and fight, sometimes against overwhelming and apparently foolish odds. This is our desire as readers.

Such power and expertise in a single character presents a great challenge for a writer. O’Brian wisely begins with Jack’s irritating eccentricities in the concert hall but, more importantly, even in the midst of Jack’s making sense of equipping the ship, O’Brian makes some of his decisions wrong, or at least ones best considered more deeply. He believes Dillon will be perfect because of his bravery in the Dart. He sees no reason to object to an oath (“No, certainly,” said Stephen. “I am not an enthusiast”). He hates necessary paperwork, “the goddamn heap of paper.” He almost forgets to lay a gold piece on the holes of the cannons for the yard. His first sail is “more like an unhurried dove than an eagle hawk.” He orders the “twelve-pounders as chasers” and tells the carpenter Mr. Lamb to “double the clench-bolts” to make them work. After they fire, there’s a foot of water in the well. His repeated thoughts begin with “if I make a mint of money,” an obsession that will later lead Dillon to confront him about his motivations and decisions as the commander of the ship. Jack might have the makings of a commander, but he is a human being.

O’Brian tempers his errors with a long and detailed catalogue of decisions. The complexity helps us give the captain the benefit of the doubt, at least for now. His humanness is paralleled by the chapter’s shorter, sometimes comic portrait of Stephen Maturin. The cosmopolitan doctor is an intellectual but does not mock Jack’s butchering of language. A less considerate companion might snort when Jack mistakes putain for patois. Stephen is not boastful (except in subsequent chapters about lost causes—being Irish and being ugly, the freedom of the human being against repressive governments). He is not too prideful to share the circumstances of his poverty with Jack. At the same time, Stephen’s expertise is impressive. He can cut up a body to determine the disease, know the qualifications of a naval surgeon, “dwel[l] on the theory of counterirritants,” know the classification of ants and toads, read medical journals, and delight in surgery. But when he meets the “nautical gentleman on the quay,” who in his patience helps him identify not the large ships, but the fourteen-gun sloop commanded by Captain Aubrey, like any other landlubber Stephen assumes the friend he had made in Jack is running his ship “fast toward the quarantine island, behind which he would presently vanish.” The faint comedy of the scene predicts the crucial role Stephen’s sailing innocence will play in the subsequent chapter.

Thankfully, Mowett finds Stephen. The bridge from land to ship is accomplished. O’Brian’s chapter has achieved its purpose. And we now are beginning to know two fascinating, very human characters.