Post Captain - An Austen Sea Yarn

The story continues

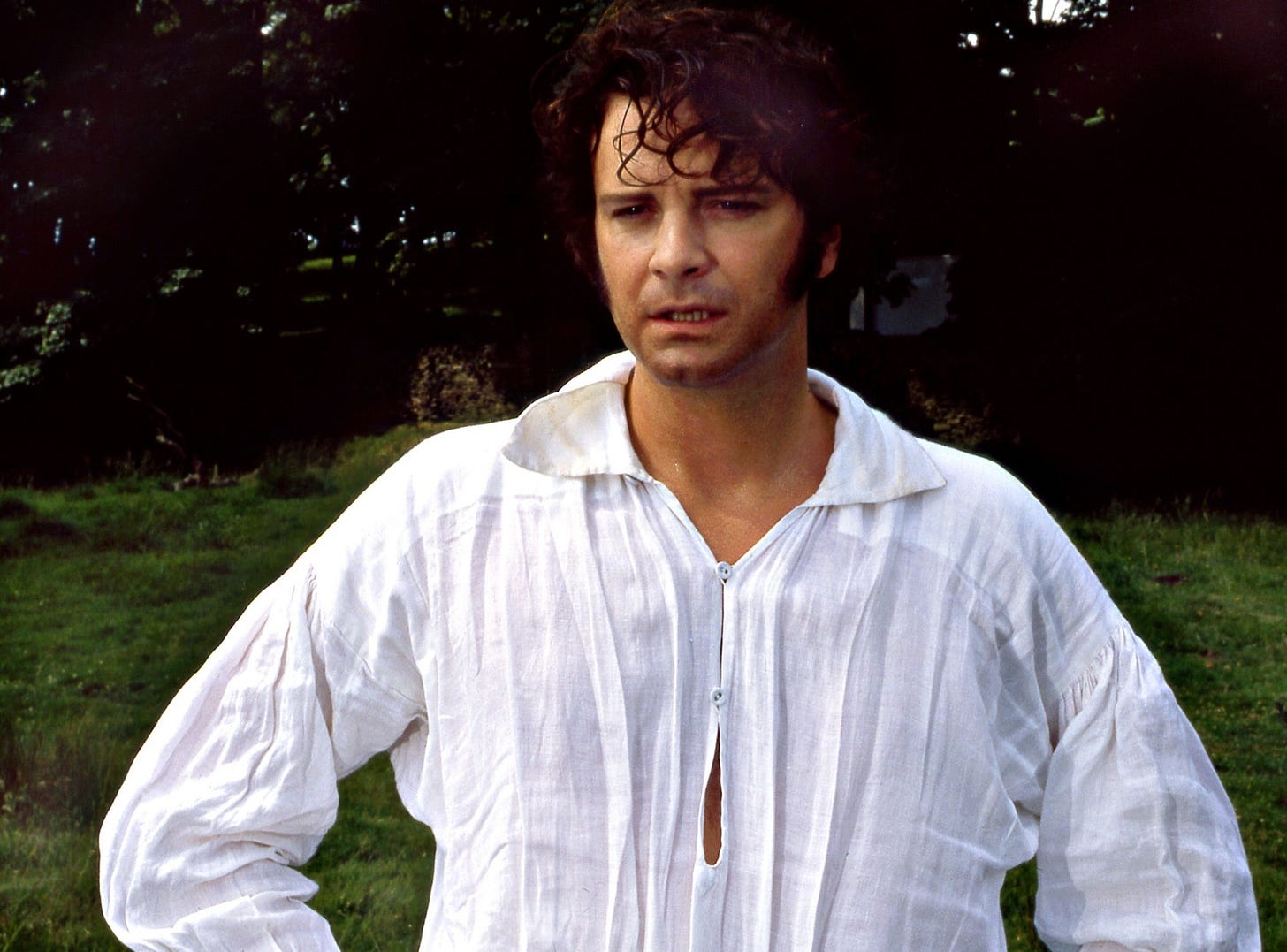

Colin Firth goes for a swim in a pond and emerges a victor in a male wet t-shirt contest. Elizabeth Bennett (a wishful Jennifer Ehle) must look away. Twenty years ago Matthew Macfadyen extends his hand to Kiera Knightley to mount the carriage and his “hand flex” becomes a TikTok dissertation on yearning. Like so many admirers of Pride and Prejudice, on my first reading of Patrick O’Brian, I remember thinking to myself what a critic from Time wrote, “If Jane Austen had written a sea yarn, it would have been Post Captain.”

On a subsequent post Evan will write of the Austen family and how much the British Navy was part of their lives. In this first post comparing the two novels, note how the problems of Post Captain echo those of Pride and Prejudice. In Austen, the father, Mr. Bennett, hides in his study, decries the silliness of his younger daughters, is bullied by his wife, and makes a tragic error in letting Lydia be so poorly watched over by the Forsters that she can run off with the duplicitous Wickham. In O’Brian, the father is not even mentioned: “Mapes Court was an entirely feminine household” (21). Not only are the two fathers ineffectual or non-existent, but there are also no brothers and a boatload of sisters—five daughters in Austen, three in O’Brian (Sophia, Cecilia, and Francis) and, to sustain a pseudo-sisterly rivalry through the rest of the story, the dark-haired cousin, a widow, Diana Villers.

Both writers are intent on closely linking two sisters, or, to be exact, in Post Captain, the eldest sister and her cousin. The pairing decreases the number of characters necessary to develop by focusing on one relationship, at first restricting it to the regions around Longbourn and Mapes Court but then sustaining it as the story reaches into Derbyshire and the City of London. In Pride and Prejudice Jane and Elizabeth deeply love each other, share secrets, and speak with an intimacy not seen elsewhere in the family. But the intimacy becomes limited, for Elizabeth must suffer knowing about Bingley’s rejection of Jane, and Darcy’s role in it, without immediately sharing the details with the sister she loves. In Post Captain, what friendship might spring between Sophia and Diana is immediately threatened. Mrs. Williams fears that Diana’s beauty and spirit might keep Sophia from making the right marriage. She “smel[ls] danger” (42) and by intermediaries and letters tries to have Diana exit the stage and remain isolated caring for a mad cousin, Mr. Lowndes, who thinks himself a teapot and is left alone by his family. But Jack hires Babbington to escort her there and provide a return so that she can attend the ball at Melbury Hall, much to Mrs. Williams’ disappointment.

As the story progresses, Diana loses patience and feels cabined by Mrs. Williams. Stephen is the most interesting and direct man she has met, a truth-teller, but she struggles with Stephen’s declaration of love and treats him abominably. “Why do you pursue me like this? I give you no encouragement. I never have. I told you … I like you as a friend but had no use for you as a lover. If you think to gain your point by wearing me out, you have reckoned short; and even if you were to succeed, you would only regret it. You do not know who I am at all; everything proves it” (254).

Instead Diana turns elsewhere. She uses her gifts of beauty, intelligence, conversation and wit (all that makes Stephen love her) to try to escape Longbourn and then Mr. Lowndes and win another rich husband. Meanwhile she flirts with Jack, who as a gentleman who has lost standing and money and is helpless before her. The subsequent rivalry between the two men bruises Stephen’s heart and disdains what Diana knows is Sophia’s true love of Jack. By some measure she rivals Wickham in duplicity. By the end of the novel we will find her in the opera box with Canning in a relationship that is mutually agreeable—he is a very wealthy Indiaman—a vision which literally freezes Stephen. The ushers must remind him that the opera is over, and everyone has left the house.

The legal problems in both novels are the same: primogeniture and coverture. Primogeniture keeps women from owning property and coverture gives whatever inheritance that might go to a woman legally to the man she marries. One of the most famous sentences in the English language—“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife”— introduces us to Jane Austen’s repeated, delightful ironic sensibility, for yes, Darcy and Bingley could use a wife for their estates, but it is the single woman who is truly in need of a single man in possession of a good fortune. She must escape the threat of poverty and, in effect, somehow survive when her parents can no longer provide for her. And thus, with so much groundwork laid 150 years earlier by Jane Austen, Patrick O’Brian writes his sea yarns contemporaneous to Austen’s great novels and in his second, Post Captain, introduces four women in search of a man of good fortune. He creates a mother who rivals Mrs. Bennet in her relentless effort to make the right match for each of her daughters.

Finally, there are the suitors. In Pride and Prejudice the soldiers come to town, and one of them—Wicklow—becomes the cad of the novel and nearly causes the ruin of each of the Bennett sisters. Jane falls in love with Mr. Bingley while Elizabeth’s prejudice leads her away from the prideful Mr. Darcy for the apparently sympathetic Wickham. But Wickham shows his true character when he runs away with Lydia, a situation solved only by the persistence and wealth of Darcy, whose character is transformed in the eyes of our brilliant heroine, Elizabeth Bennett. She understands her own ill-founded prejudice, while he diminishes his insulting pride.

In Post Captain the sailors come to nearby Melbury Lodge. Let the partying begin. Let the romance begin. Jack Aubrey falls in love with Sophia, Stephen Maturin with Diana Villiers. But it is property and primogeniture that move the plot. The prize courts don’t grant Jack the prize money he deserves, and his spending habits drive him into debt and, suddenly, his worthiness as a potential husband fades, for he is a single man in possession of no fortune and in fact is threatened by debtor’s prison. He allows himself to fall into a never specifically delineated but clearly improper relationship with Diana, who as a widow without a mother controlling her has connections outside the Williams family and can move about with more freedom than Sophia. Diana is still in search of a man with a good fortune. Meanwhile, both Sophia and Diana recognize that Stephen Maturin, while an ugly and odd man, is remarkable. What they don’t know about him is slowly unveiled in this and subsequent novels. We discover his wealth, his scientific reach, and his dangerous work for the government. We marvel at his effort to maintain a friendship with a clueless Jack even as the post captain betrays their intimacy as friends.

I am certainly not a scholar of Austen or of O’Brien, but a lover of both and a scribbler myself. We see how O’Brian feels Austen’s influence in creating his story. The next time I’d like to investigate that most difficult of techniques, the use of irony.