Post Captain culminates in the action of October 5, 1804, sometimes called the Battle of Cape Santa Maria, in which four British frigates successfully attacked four Spanish frigates carrying specie from South America. The novel does a good job explaining the context: Maturin gets intelligence that the Spanish are going to join the war after the specie arrives, so the British attack first. Aubrey commands the Lively, one of the four frigates, and the novel ends with high hopes that his financial troubles are at an end because of the prize money windfall.

The real story isn’t much different. O’Brian puts the intelligence in the hands of Maturin rather than Alexander Cochrane, who was the naval officer who told the Admiralty about the specie. O’Brian also swaps out Captain Graham Hamond of the Lively for Aubrey, who holds temporary command. In real life the Lively was newly-built in 1804, the first of a successful class of 18-pounder frigates; in the book, Lively has been in the East Indies for several years, bringing her crew to a level of sailing efficiency that stuns Aubrey. But those are pretty minor tweaks, all told. If you want a narrative of the battle, read Post Captain—it’s as good and as accurate as you’ll find.

O’Brian also mentions one of Britain’s two mistakes that lead to the tragedy of the explosion of the Mercedes, one of the Spanish ships. The first is that the navy really should not have sent an equal force. The Spanish had no idea that they were being targeted and were entirely unprepared to fight the British. As Maturin tries in vain to explain, had the British sent an overwhelming force of ships of the line, it would have been easier for the Spanish commanding officer, José de Bustamante, to surrender without a fight, saving several hundred lives including many women and children who were passengers aboard the Mercedes.

There weren’t many spare ships of the line to send, though, and that gets to the second British mistake. In 1804, Napoleon was massing an army on the English Channel. He had enough naval forces on his own to challenge British command of the Channel, if he could only get them there—they were spread around France and Spain from Toulon to Ferrol to Rochefort to Brest. Adding the Spanish navy to the French navy dramatically worsened Britain’s strategic situation. Rather than pre-empt the Spanish, the British should have done everything possible to keep the Spanish neutral. Maturin wants the Spanish in the war so he can work toward Catalan independence, and O’Brian doesn’t have an independent voice to argue this point and thus passes over the mistake in the narrative.

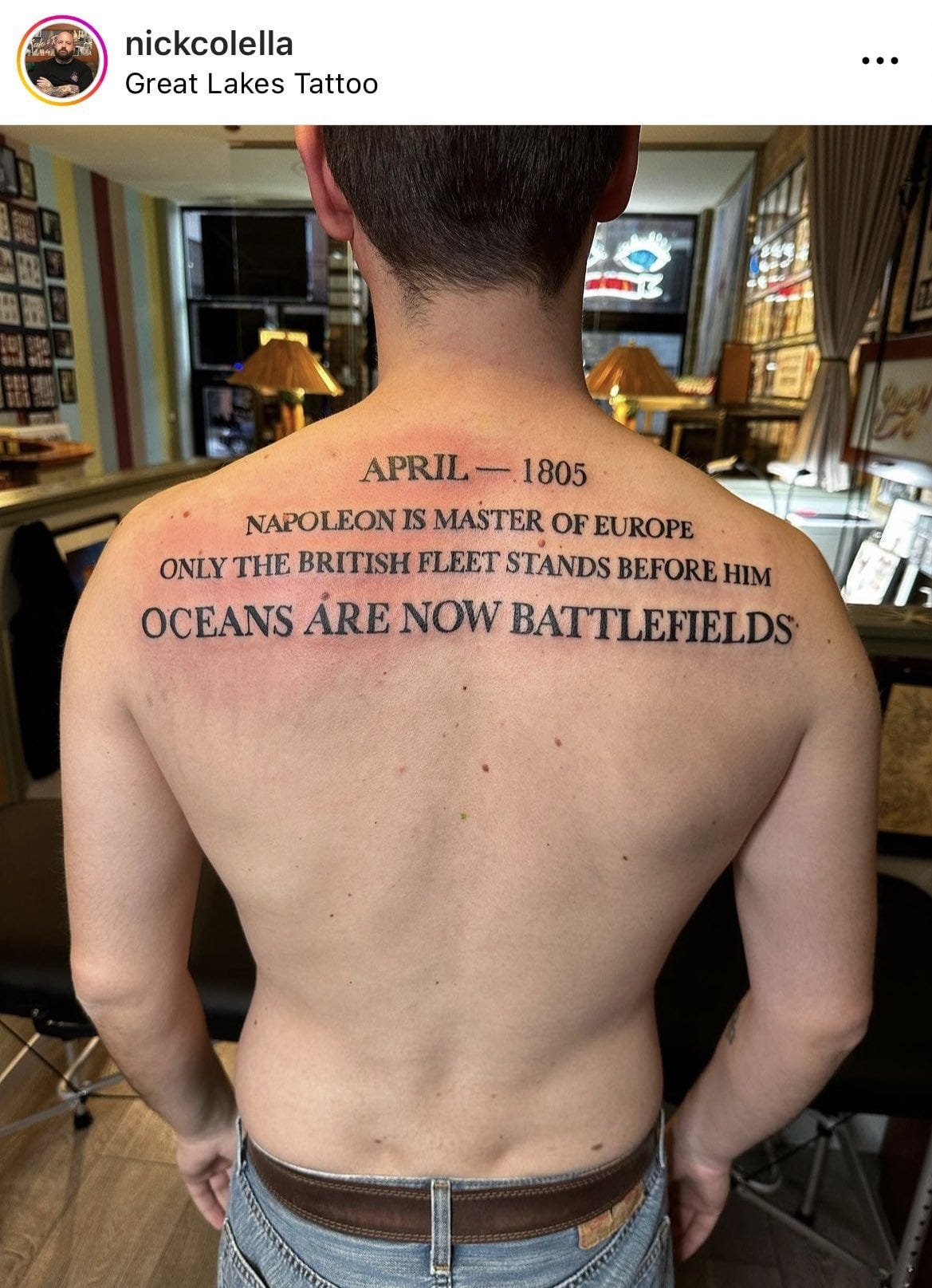

The result of this second mistake was the Trafalgar Campaign of 1805. The Spanish joined the French in the winter of 1804–1805, combining their naval forces so that they outnumbered the British. In the spring of 1805, well, you know this part already:

[As an aside, oceans are NOW battlefields? What were they before? Sorry—never go to the movies with a historian.]

There were several close calls in the Trafalgar Campaign when Napoleon’s complicated schemes to launch a cross-Channel invasion almost worked. Could the French and Spanish could have held command of the Channel long enough to get an army across? It’s hard to say, but many British naval officers thought it was possible. In the end, the schemes failed, Napoleon packed up his army to fight the Austrians, and Nelson destroyed the Combined Fleet at Trafalgar.

If you want more, here’s a lecture I gave on the subject to the Redwood Library in Newport during Covid:

The point is, the reason Nelson was fighting both French and Spanish ships at the famous battle is because of the events of October 5, 1804, as depicted in Post Captain.

This preemptive strike is one of several examples of British actions in the Napoleonic Wars that violated the laws of war, or at least tested their boundaries. In 1807, the British struck preemptively against neutral Denmark to deny Napoleon the use of their fleet. The Danes are still (understandably) angry about this today, especially since the British bombarded civilians in Copenhagen as part of the action. The same year, HMS Leopard stopped, fired upon, and boarded USS Chesapeake to search for deserters. The Jefferson administration decided not to declare war in response, even though it was clearly an act of war.

The British continue to defend these actions on the grounds of necessity: the Spanish were going to join the war anyways; Napoleon was going to use the Danish fleet; the US Navy was full of British deserters. I’ll leave it to readers to judge for themselves whether those defenses hold up under scrutiny.

Next week I hope to have another post on the Battle of Cape Santa Maria, relying on archival accounts of the captains involved.