HMS Surprise - Really?

The Unbelievable Stephen Maturin

Why do some characters jump from the page into our memories? Here’s a few with staying power on my reading list. Odysseus and Antigone. Guinevere. Macbeth. Gulliver. Micawber. Doroetha Brooke. Tess. Jo March. Huck. Jim (James). Ahab. Gatsby. Leopold Bloom. And that’s enough but certainly not all. The question is, why do the characters you’ve read in books continue to live?

Characters who linger in memory push credulity. Before we grow skeptical about Odysseus’s escapes from peril or Dorethea Brooke’s idealism, an author needs to win us over quickly, either by our immediate delight in the person’s wit or beauty (Elizabeth Bennett) or by our fierce distaste (Fitzwilliam Darcy), or by some potentially violent or mysterious act involving a character that catches our imagination or fear (the witches’ brew and prophecy in Macbeth). Then Coleridge’s “willful suspension of disbelief” quickly kicks in, for something inside our humanity wants to be entertained, even if the entertainment strains credulity.

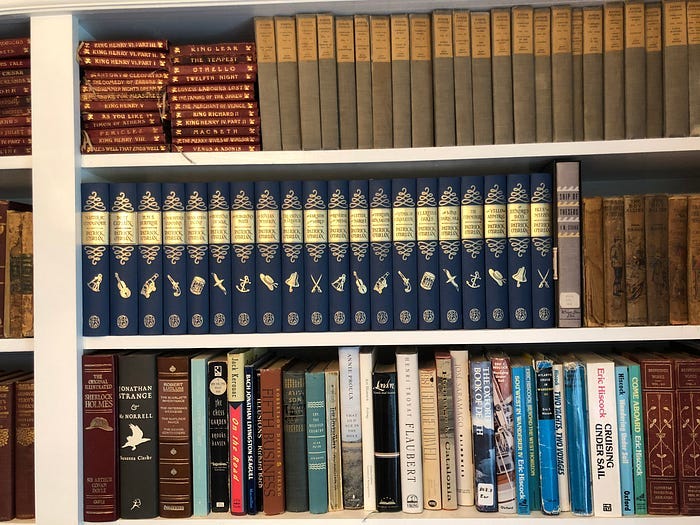

Does the Maturin/Aubrey series still fascinate 25-50 years after publications? It continues to sell! Hardbacks, paperbacks, and e-books, and millions in multiple languages are available. And they appear in omnibus editions. I suspect most of them sit on bookshelves not because of their decorators’ colors or the heft of standing next to the Folio Society or the Oxford Shakespeare but because readers still like a good yarn. Yes, they are grippingly good yarns, but I believe at least the first three are more than that (not to denigrate in any way a good yarn). They are more complex, memorable, and lasting than only high seas dramas.

Consider Stephen Maturin in HMS Surprise. He is often referred to as a natural philosopher, a phrase first used in the fourteenth century that encompasses many (but not all) of his occupations:

Surgeon – When Stephen tries to convince Jack that medicine cannot save most lives, Jack can only remember that he has seen Stephen trepan the gunner of the Sophie. He watched Stephen saw a hole in the man’s skull and expose his brain and like every sailor who witnessed decides Stephen is the best surgeon in the fleet and even a miracle worker.

Physician – that is, a doctor not using a hacksaw. In diagnosing the scurvy in chapter 5, as in previous diagnoses, he is exact and scientific. He sees the sailors’ “weakness, diffused muscular pain, petechia, tender gums, ill breath.” (Petechia is “a small, flat, red or purple spot caused by bleeding into the skin or other organ.”)

Pathologist – what great delight Stephen takes in taking apart a dead baboon in Madras. A corpse will also do.

Experimental scientist and naturalist – Stephen has moved from bees on his last voyage to raising rats on this one and feeling them with madder (a plant used for dye) “to see how long it takes to penetrate their bones.” On the jolly boat trip to the island with the unfortunate Nicolls, Stephen fills his boxes with several specimens before the storm shocks them.

Linguist – on the same jolly boat he practices his Urdu phrases and tells Nicolls about the various dialects in India.

Entomologist – Stephen meets Sir Josph at the Entomological Society meeting in London.

Freedom fighter – Stephen hates Napoleon so much that as an Irishman and Spaniard he is willing to work for Britain to defeat the tyrant. In this novel he meditates at length on leaders and government: “there must be the far rarer quality of resisting the effects, the dehumanizing effects, of the exercise of authority” in order to be a good leader.

Spy – without question Sir Joseph Blaine and Lord Melville think Stephen is the best spy working for Britain. They gave him the rank of captain on the Lively, an honor given only to two people previously, one of whom was Sir Joseph Banks.

Marksman – “The enormous impact on his side and across his breast came at the same moment as the report. He staggered, shifted his unfired pistol to his left hand and changed his stance: the smoke drifted away on the heavy air and he saw Canning plain, his head high, thrown back with a Roman emperor air. The barrel came true, wavered a trifle, and then steadied: his mouth tightened, and he fired. Canning went straight down” (347).

Imagine, if you will, that you’re a prosecuting attorney intent on proving that Stephen Maturin cannot be a real human being. You might begin your argument simply enough. “I mean, really?” you might say to the jury, “One man can be the most successful surgeon in the fleet, diagnose every disease from scurvy to gonorrhea, dissect apes or dead humans, speak four languages, be compared at times to the inimitable Joseph Banks, know the name of everything that crawls, risk his life to depose Napoleon, convince a genteel young woman (Sophie) to make him her closest friend, inform the Admiralty of the disposition of Spanish and French ships and the spies of those countries, and after being hit by a bullet, move his gun to his left hand and shoot a man dead.”

We accept O’Brian’s acknowledgment that in creating Jack’s adventures in battle, he made him part of multiple actions no single British sailor could have possibly been part of. If the actions were completely imaginary—the stuff of fiction—perhaps we wouldn’t even raise the question, but the more we read in the series we realize that O’Brian used real events. He made Jack’s place in them a fiction. It might be good to remind ourselves that meanwhile the surgeon Stephen Maturin is below decks surviving all these actions and the good doctor is damned lucky he survived them all, including his sometime presence on deck. Really? It strains credulity.

So why do we suspend disbelief?

The virtues O’Brian uses are ones that resonate in adventure stories—spy, marksman, diarist, man of luck, and lover—and for centuries impossible adventure stories have captured readers. The romance between Stephen and Diana is equally as important as Jack and Sophie’s because of its unlikeliness, another fictional technique we love. Who doesn’t want to imagine an extremely beautiful person falling in love with ugly ol’ me? Stephen’s “ugliness” is emphasized and it’s comic. He is constantly in danger of falling into the sea and even struggles with port and starboard. He is irascible and can’t stand being helped, which has to happen a good bit. He is ugly. He embarrasses the crew by his nakedness. He cherishes a tortoise. He is proud that he has taken 420 strokes to swim the length of the Surprise, which Jack calculates is a stroke per three inches of water. O’Brian’s crucial technique in making Maturin the character who lingers in our minds is how comically important his foibles are to his characterization. And, by the way, he is obsessive, doing as much research on the voyage to India about Diana and Canning as he does about French spies.

O’Brian’s genius of characterization in HMS Surprise touches our hearts in the end when this hard-to-believe man extends his great, soulful generosity to Dill only to find out that the bracelets he gave her causes her death. “He picked her up, and followed by the old woman, a few friends and the Brahmin, he carried her to the strand … the pyre was no more than a dark patch with the sea hissing in its embers; and he was alone” (238).

But our hero, who we embrace in all his complexities, suffers even more.

“My name is Maturin,” said Stephen. He recognized the hand [the address on the letter], of course, and through the envelope he felt the ring [his engagement to Diana] … he walked steadily uphill up … through the trees … There was a little sleety snow lying in the shadows up there, and he scooped handfuls of it to eat; he had wept and sweated all the water out of his body; his mouth and throat were as dry and cracked as the barren rock he sat on … The dislocated elements of memory fell back into place: he nodded, buried the ancient small iron ring that he had still clasped in his hand … and found a last patch of snow to rub his face.”

Before rowing back to the ship, Stephen tells Jack: “Diana has gone to America with a Mr. Johnstone, of Virginia: they are to be married. She was under no engagement to me—it was only her kindness to me in Calcutta that let my mind run too far: my wits were astray. I am in no way aggrieved; I drink to her.”

We drink to Stephen.

i love this. i’d add that the 400 zillion volumes ought to be considered as one “book”. this really allows O’Brian (I think that’s the correct spelling btw) to stretch out and develop the characters.

Spanish or specifically Catalan? Or am I just confused by his collection of languages? Though I must admit that before the Spanish Civil War captured my interest I would not have recognized the difference myself.