I learned recently that I missed a trick when writing The Horrible Peace. It’s a long walk to get to where we’re going, so please be patient.

Karl Marx famously quipped, “Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.” He went on to compare the characters involved in Louis Bonaparte’s coup of 1851 with those of the French Revolution. The latter was a tragedy, the former a farce.

Marx’s quote is usually reworked to say something like, “History repeats itself—the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.” It’s frequently trotted out without any context, but I’m not here to do what you probably expected me to do, and provide context for Marx’s quote. Instead, I’m going to be more annoying: I’m going to track down Hegel’s original.

(Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel was a German philosopher born one year after Napoleon.)

Hegel actually meant something different (hence Marx’s “remarked somewhere” and “so to speak” and “forgot to add”). What Marx was riffing on was Hegel’s recounting of the assassination of Julius Caesar. Hegel argued that:

[Cicero, Brutus, and Cassius] believed that if this one individual [Julius Caesar] were out of the way, the Republic would be ipso facto restored. Possessed by this remarkable hallucination, Brutus, a man of highly noble character, and Cassius, endowed with greater practical energy than Cicero, assassinated the man whose virtues they appreciated. But it became immediately manifest that only a single will could guide the Roman State, and now the Romans were compelled to adopt that opinion; since in all periods of the world a political revolution is sanctioned in men’s opinions, when it repeats itself.

Hegel’s version isn’t nearly as punchy, and as I mentioned, it really does mean something different. As John Ganz summarized, “In other words, assassinating Julius Caesar could never work: the world itself was changed; this one particular individual could be done away with, but his type of rule was here to stay.”

But what caught my attention was what Hegel said next, to illustrate his point further:

Thus Napoleon was twice defeated, and the Bourbons twice expelled. By repetition that which at first appeared merely a matter of chance and contingency becomes a real and ratified existence.

That would have been a really useful framework for me to tell the story of the end of the Napoleonic Wars! That’s what I meant in the first sentence of this post, when I said I missed a trick. I could have deployed Hegel and I think that my readers would have understood what I was talking about, which is rarely the case when Hegel is involved.

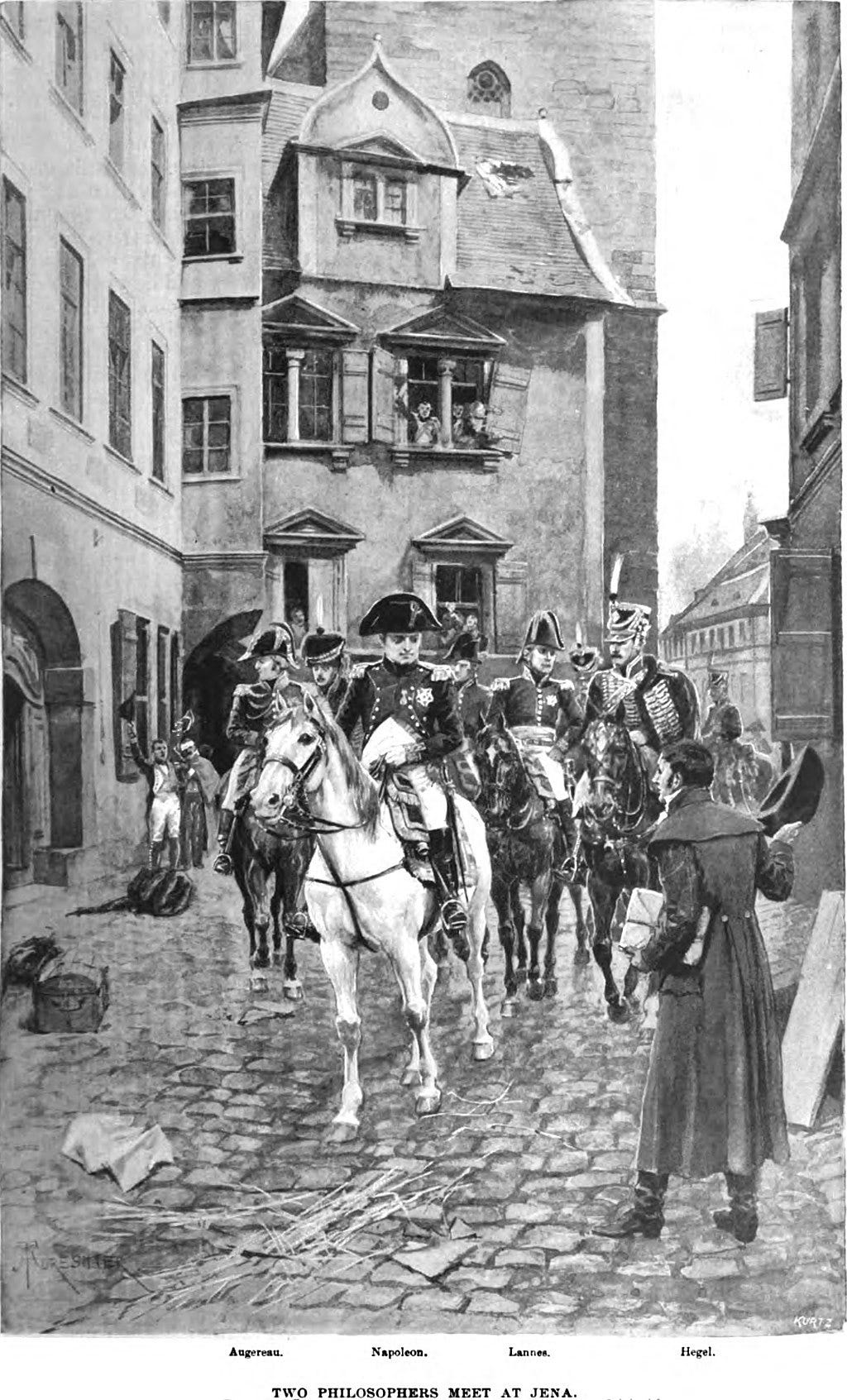

Hegel famously told a friend after he saw Napoleon in 1806, “I saw the Emperor—this soul of the world—go out from the city to survey his reign; it is a truly wonderful sensation to see such an individual, who, concentrating on one point while seated on a horse, stretches over the world and dominates it.” But Napoleon’s abdication in 1814 showed that it was possible to imagine a world without him bestride it. Similarly, the Bourbons were doomed by their own absence from the world stage, both after Louis XVI’s execution in 1793 and again when Napoleon returned from Elba in 1815. They were inessential and replaceable, and more importantly, it did not take any imagination to think about France without them.

I will leave it to readers to apply this Hegelian argument to our present political crises.1 At the very least, though, now you (and I) know that when you see Marx’s quote about tragedy and farce trotted out, you know that he’s riffing on Hegel who was actually talking about Caesar, Napoleon, and the Bourbons.

I am not endorsing Ganz’s application of Hegel’s ideas, but I am indebted to him for the idea for this post.

The basic idea has occurred to me multiple times since 2015....