Applied History

An anatomy

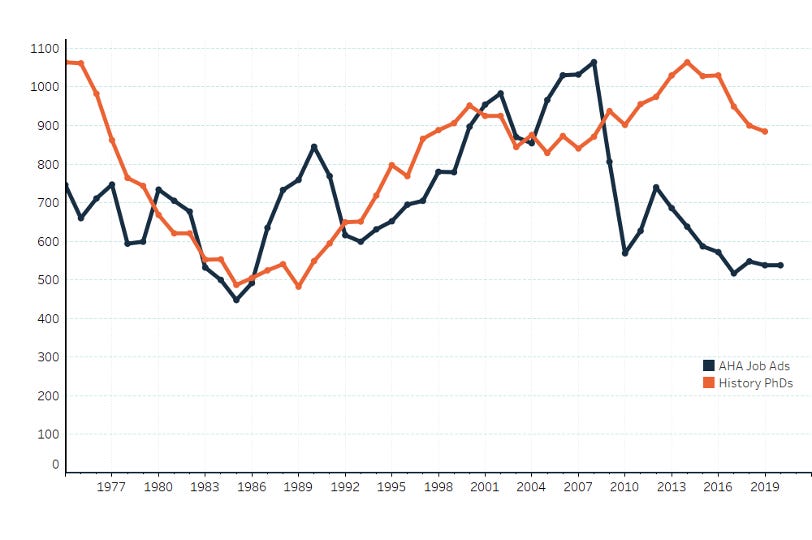

It’s become such a cliché to talk about the crisis in the humanities that now the first two results on Google for “crisis in the humanities” are people saying “stop talking about the crisis in the humanities.” But from my perspective, there are still plenty of reasons to be alarmed. There are fewer majors every year, and there’s a smoking crater where the academic job market used to be:

If you want the gory details of the job market, Bret Devereaux has you covered. And all that was true before you even think about the threat from large language models.

These overlapping crises have spawned a thousand ideas for how to respond. One such idea is the newly-established applied history fellowships at the Institute for Historical Research. As the advertisement explains, the fellowships are aimed at “three pressing challenges”:

the need to build sustainable bridges across different parts of the history community

the deeply challenging academic job market

the need to advocate for the utility of history beyond the [Higher Education] sector.

I am very lucky to have a job, but I too am feeling pressure to “advocate for the utility of history.” Among my civilian academic colleagues, the idea is to make studying history as useful as majoring in business or communications; in professional military education, the idea is to make history useful to policymakers.

So in this post, I want to try to unpack the fashionable term “applied history.” I’m doing this mostly for my own edification, but perhaps you will also find it interesting—or, I should say, useful.

Applied History as a Sub-Discipline

Applied history is not new, but the most recent iteration derives from the 2016 “Applied History Manifesto” published in The Atlantic by Harvard’s Niall Ferguson and Graham Allison. I’m going to go line-by-line through their first paragraph:

Applied history is the explicit attempt to illuminate current challenges and choices by analyzing historical precedents and analogues.

To a non-academic audience, I suspect there’s nothing unusual in that sentence—it makes sense to try to leverage historical study for present-day concerns. You might look for lessons, or you might take the “history doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes” approach.

Academics read it slightly differently because of the word “explicit” and because we get nervous when people start rhyming. Let’s keep going to figure out why:

Mainstream historians begin with a past event or era and attempt to provide an account of what happened and why.

Any attempt to describe an entire discipline in one sentence is going to open itself up to exceptions, but I’m not going to focus on that. I can’t get over the first word, which immediately suggests that applied historians are setting themselves deliberately apart from the rest of the academy. Sure enough:

Applied historians begin with a current choice or predicament and attempt to analyze the historical record to provide perspective, stimulate imagination, find clues about what is likely to happen, suggest possible policy interventions, and assess probable consequences.

Consider my hackles raised. Here are three reasons:

We can’t address the crisis in the humanities by subdividing ourselves further, into “mainstream” and “applied” camps. I much prefer the applied history fellowship advertisement that I quoted earlier, which calls for applied history to build bridges across the historical community.

There’s already a discipline that looks at the present and future and then mines the past to provide guidance to policymakers: it’s called political science. Political scientists create knowledge deductively, by developing theories of how the world works and testing them against the historical record. I am skeptical of the idea that historians will flourish if we tread on political scientists’ turf.

Historians create knowledge inductively, by studying the historical record and then trying to make sense of it. There are lots of historians who recoil at the idea that the present should guide our research. Sir Herbert Butterfield put it like this: “The study of the past with one eye upon the present is the source of all sins and sophistries in history. It is the essence of what we mean by the word ‘unhistorical’.”

Ultimately, though, I’m not in a position to dismiss applied history. Not only do I need to think about it in my day job, but I don’t want to commit the same sin of dividing our forces in the face of the enemy. We need all the allies we can get at the moment.

There’s also something deeply, fundamentally honest about the applied history manifesto that all historians need to think about, which is that of course historians “begin with a current choice or predicament.” Historians can’t do history from any other time period than the present, because that’s the time period in which we all live! That means our work is inevitably shaped by the present.

History is what the present wants to know about the past. The challenge is to understand the role the present plays in our studies, suspend that as best we can, and then look at the past on its own terms.

A Middle Path?

Graduate school trains most people like me to aim for that suspension of the present. The Navy, an organization that is relentlessly practical and future-focused, wants me to do the opposite. I think there’s a middle path, between history for history’s sake and full-on political-science-lite applied history.

I recoil at the idea that my research can produce lessons. I’m even suspicious of the idea that history rhymes. My go-to cliché quote is different: “The past is a foreign country. They do things differently there.”

But I have had some luck in studying the past to generate questions that we might want to consider today. That approach treats the past not as a guide to the future but rather as an enormous storehouse of knowledge and experiences that broaden our horizons and provide essential context. When we study the full sweep of the human experience, we can draw on it to identify issues that we might not have otherwise considered.

Since I’ve worked for the Navy, I’ve used my research to ask policy-relevant questions about seams in areas of responsibility, about the challenges of war termination, about the difficulties of transitioning veterans to civilian life, about the dangers of fighting the last war, and about who might come to a war college in wartime. Asking questions, it seems to me, allows decision-makers to maintain their focus on the present and future while still encouraging them to see their current predicament from a historically-informed and sometimes novel perspective.

I completely understand why decision-makers want historians to tell them how to apply the past to solve their problems, or at least to “assess probable consequences,” as the manifesto put it.1 I don’t think I can do that. All I can do is encourage decision-makers to support historical scholarship so that we can all understand that the past was different while also benefitting from the vast repository of human knowledge that history can provide.

I also understand why it might be lucrative to market yourself to powerful decision-makers as being able to use history to assess probable consequences.

Greetings Evan.

Interesting post, I’ve been seeing your posts pop up for quite a while now.

Given what you share, i thought you may enjoy what I do.

I share a look at obscure histories, the ones left out of mainstream interpretations.

Here’s my latest, continuing on in my recent series regarding Giants:

https://open.substack.com/pub/jordannuttall/p/a-historical-record-of-giants-2?r=4f55i2&utm_medium=ios