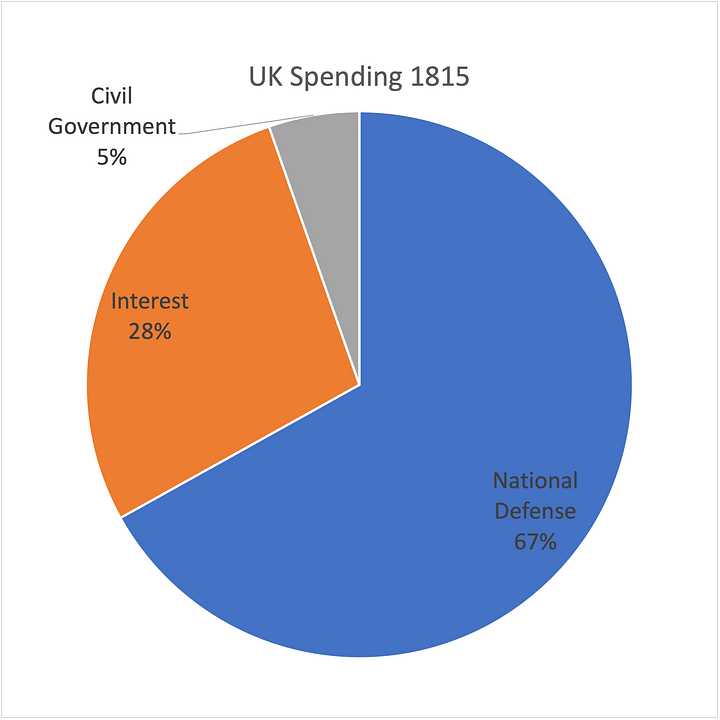

On the left is a simplified picture of the British government’s spending in 1815; on the right is an even-more-simplified picture of the US government’s spending last year.

The one-liner about the US government today is that it’s an insurance company with an army. The 1815 British government was basically just an army. There was no social insurance, no national health service, no public education.

My plan for the next three posts is to look at some of the implications of this observation. This week, I’m going to dump some data on you and ask whether Britain benefitted from a “peace dividend.” As always, there’s much more in the book. Buy, subscribe, share, in some order, if you’re enjoying all this.

The debt comes first

Not only did Britain in 1815 spend a lot more of its budget on its military than the US does today, but it also spent a lot more servicing its massive debt (the orange pie slices above). This is the ratio of public debt to GDP in Britain since 1692:

The Napoleonic Wars are the peak of the first mountain range. The costs of the wars caused the debt to grow to more than twice the value of all the goods and services produced in the country. That’s comparable to the debt incurred to fight the two world wars in the twentieth century (the second mountain range).1

Across the eighteenth century, Britain’s ability to borrow this much money was its greatest strength. No other country could sustain that kind of public debt without defaulting on it. In one sense, this chart is a story of Britain’s success.

But put yourself in the shoes of Lord Liverpool, the prime minister in 1815. Remember that you don’t know that the next century will see a steady reduction in debt. This is what you know:

How confident would you be that this debt, which had tripled since the beginning of the wars, was sustainable? When your finance minister told you that half of the government’s budget in 1816 would have to be given over to interest on the debt, how would you respond?

Slash and burn

Unsurprisingly, Liverpool answered: cut. Cut everything. And as we saw in the first chart, “everything” meant the military. The government’s (understandable) goal was to get its balance sheet in order as fas as possible. And that’s exactly what happened. Here’s defense spending for the postwar decade:

The army’s budget was cut by about 80% and the navy’s by about 75%. Those are real cuts, with real consequences (which I plan to discuss in next week’s post). The closest modern parallel is this:

That’s US defense spending during and after the Second World War. Similar curves, right? And that shouldn’t be surprising. In both cases, we’re talking about victorious countries who transformed their economies and societies to fight global wars. The number one priority in the postwar years for anyone looking at the budget had to be cutting the armed services, which clearly didn’t need to be as large as they had been during the wars.

A peace dividend?

In the US in the twentieth century, postwar defense cuts seemed to provide an opportunity. All the money spent on guns could be spent instead on butter: in other words, the country could reap a “peace dividend” that could be redistributed to social services, healthcare, education, etc. The phrase itself became part of the national conversation during and after Vietnam, though of course similar ideas circulated after the Second World War—think of the G.I. Bill. But as this Google n-gram shows, “peace dividend” became a common term at the end of the Cold War, and it’s often associated with President George H.W. Bush:

Reagan’s massive military spending in the 1980s, it was assumed, could be reduced and repurposed now that the Soviet Union had collapsed. But Bush rejected that framing in a televised address in September 1991:

But the United States must maintain modern nuclear forces, including the strategic triad, and thus ensure the credibility of our deterrent. Some will say that these initiatives call for a budget windfall for domestic programs, but the peace dividend I seek is not measured in dollars, but in greater security. In the near term, some of these steps may even cost money, given the ambitious plan I have already proposed to reduce defense spending by 25 percent. We cannot afford to make any unwise or unwarranted cuts in the defines budget that I have submitted to Congress.

In fact, Bush was so focused on security rather than dollars that defense spending actually increased from 1991 to 1992 as a percent of the budget:

It fell under Clinton, as you can see. I’m pretty far out of my lane here, so I’ll leave it to others to explain whether the cuts to defense resulted in an increase elsewhere that we might identify as an end-of-the-Cold War peace dividend. In general, though, I’m skeptical that peace dividends live up to their promise. Transitioning from war to peace often causes recessions and social disruptions that impede a simple transfer of military spending to domestic programs. Certainly there was no peace dividend in 1815, as the title of my book suggests, and as it discusses in great detail.

For the purposes of this blog, though, I was struck by Bush’s reframing of the peace dividend in 1991 to mean an increase in security rather than an increase in shared prosperity. That seems to be a tension worth exploring in future posts, both from historical and contemporary perspectives. Was there actually an increase in security after 1815? What are the risks associated with cutting the military so deeply? I also plan to look at continuities in conservative ideology—Bush was not the first conservative leader to reject the idea of reallocating military spending for social programs. More to come.

I’ve been looking at versions of this chart for many years now; in some versions, the debt to GDP ratio in 1815 is greater than it was in 1945; in others, like this one, it’s slightly lower. As far as I can tell, it changes based on economic historians’ guesstimates of GDP in 1815. The point is that there was a lot of debt.

I’m not an economist but a lifelong student of history and believe that all of our spending needs to be cut. If we ended foreign aid, quit looking for proxy wars and financing them and paid our debt down while returning money to the taxpayers we’d be a happier nation. Think of the infrastructure that needs maintenance, how families and individuals would benefit from paying reduced taxes or even eliminating taxes on a significant scale. Our current system system is untenable.