How to Conduct Archival Research

Busting some myths

Nota Bene: I know many of our readers are professional historians. This post is not aimed at you.

As I mentioned a few weeks ago, I’ve been going to various nearby archives to exploit smaller collections related to my current research. In casual conversations about these visits, I’ve learned that there are several common misconceptions about how, exactly, I go about conducting these visits. This post attempts to pull back the curtain a bit.

I hope it also makes clear how much historians rely on archivists and archives to do their work. There’s a reason most historians make a point of saying “thank you” to archivists in the acknowledgements of their books. We literally could not do what we do without them!

Who is allowed to look at documents?

Put another way, do you have to be a fancy historian to look at archival documents? Not usually. Most archives are open to the public at no cost. Government archives like the US’s National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) or the UK’s National Archives at Kew are open to the public by law—the documents they hold were largely produced by your tax dollars, so they are required to provide you access to them so long as they aren’t classified. Universities and local record offices operate in the same way even if they aren’t required to by law: the whole point of an archives1 is to facilitate access to the materials inside. I’ve never encountered an archives with an entrance fee.

Occasionally you’ll find archives that won’t let you in until you’ve proven that you’re there for serious historical reasons.2 Once I had to write a letter and mail it to a British university requesting access, stating my credentials and the project I was working on, just so that they could mail me back a letter saying “ok,” which I then had to bring with me when I visited the archives. That was silly. That was also unusual.3

The bottom line is that if you want to look at old documents, you probably can.

How do you know what documents are in an archives?

Online catalogues vary in quality and ease of use, but most archives provide some way for you to look for documents in advance. Once you identify what you’re interested in, you usually request the documents in advance of your visit by creating a free online account and clicking a “request” button. You often need to schedule an appointment as well—the best systems combine these two actions into one. Larger archives often require that you bring proof of your address so they can issue a reader’s card.4

One of the most frustrating parts of my recent visit to Harvard was that the online system allowed me to request as many items I wanted for any date I wanted … and then a week before my visit I got an email from the archives saying that 1) I didn’t actually have an appointment because appointments went through a different system and 2) I was allowed to request only 6 items, so they preemptively cancelled some of my items (without asking which ones) to get me down to 6.

At NARA, the online search tool is so unwieldy that it’s common to show up with a vague idea of what you need but not a specific document ordered for your visit. You speak with a subject-specialist archivist when you arrive who helps you figure out what you are actually looking for, sometimes using a paper catalogue to help. At Kew, the opposite applies: the online system is so robust that you rarely need to speak to an archivist.

What happens when you get to the archives?

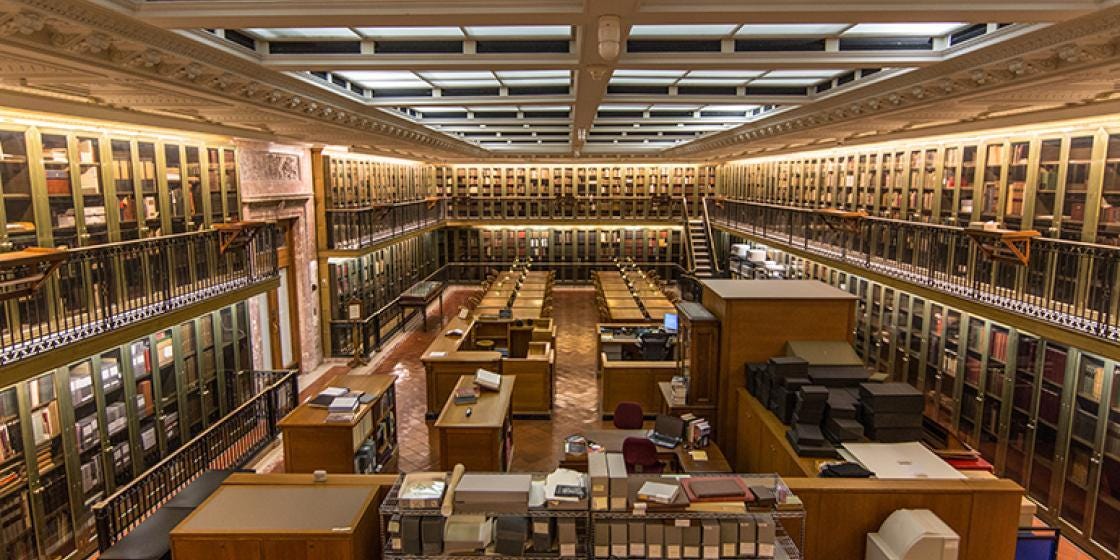

Reading rooms are often grand affairs:

But sometimes they’re as simple as a room with a table and a few chairs. Archivists monitor the reading rooms in person and sometimes on CCTV to make sure you’re following the rules and handling the documents properly.

In the bad old days, archives had a wide range of policies about cameras. These days, with a few annoying exceptions, most archives operate with the same rules. You can bring a camera (usually your phone) and a laptop inside the reading room. Almost everything else is forbidden: definitely pens, sometimes pencils, often notebooks, always water and food. All of that stuff goes in a locker or in a different room from the reading room.

I was frustrated at the British Library a couple of years ago to discover that some documents I wanted were listed as “no photographs allowed.” I never did figure out why. Most archives in most cases, though, will let you take as many pictures as you want. I always bring my phone charger for that reason—taking a few hundred pictures does a number on your battery.

(Kids: it used to be the case that phone cameras were crappy, so historians would invest in nice digital cameras. I have owned several for this express purpose. In those days we also cared about things like camera stands. No more.)5

Inside the reading rooms there’s a desk where archivists process your requests. In smaller archives, they’ll ask you which documents you want to see and bring them to your table. Sometimes they all come out on a cart; other times they’ll be brought to you one box at a time. At Kew, you have a locker with your documents in it that corresponds to your assigned seat, so you retrieve your own documents in whatever order you prefer.

How do you handle the documents?

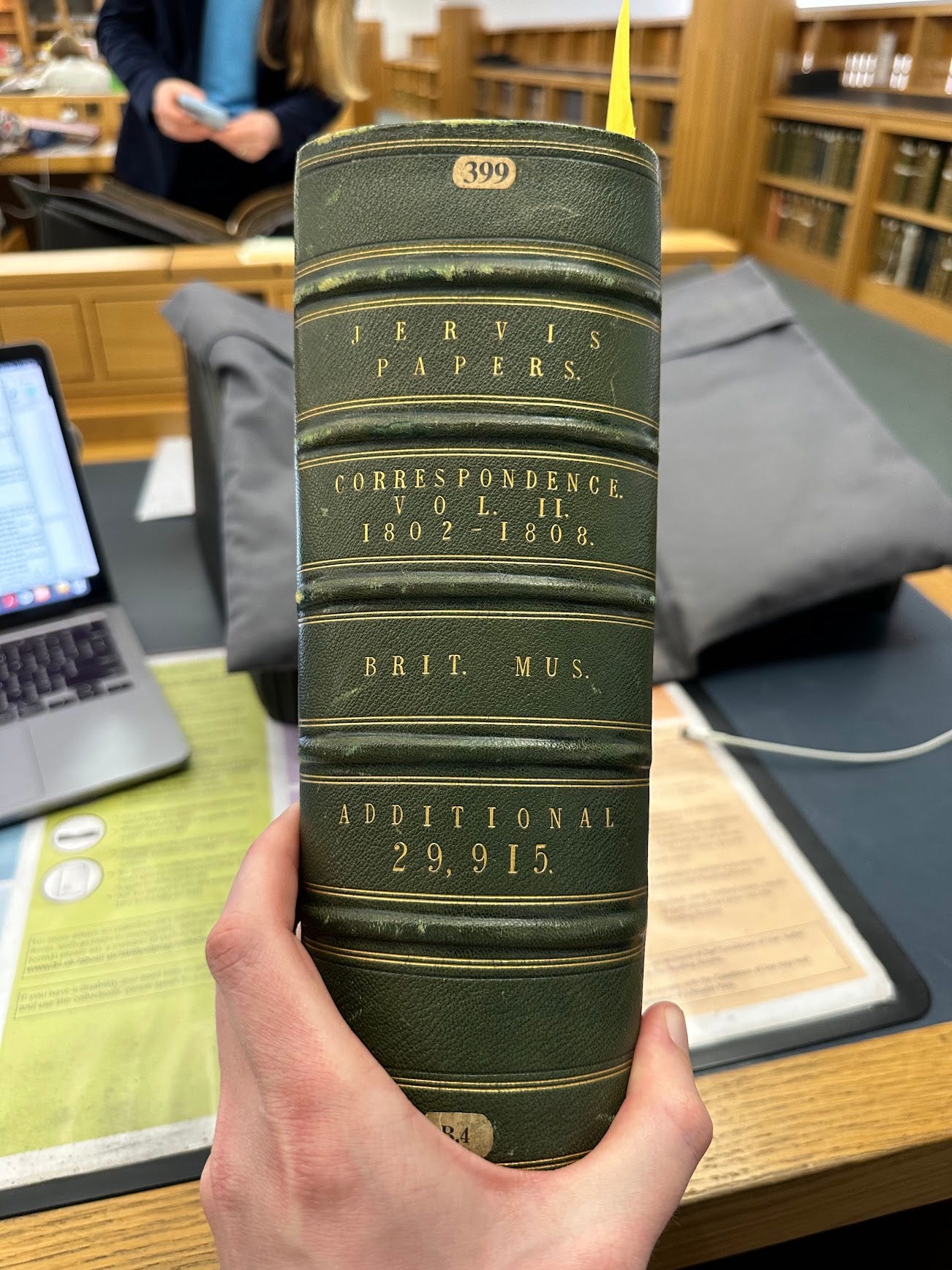

The whole point of this exercise is to find yourself sitting at your (often assigned) seat with a box or book sitting on the table in front of you. Now what? Well, you open it up and get to reading. Archival boxes vary in size, shape, organization, durability, ease of use, and so much more. Medieval documents often come in large rolls; eighteenth-century documents are often in heavy bound leather books; maps come in giant folders. What is in front of you depends on what you asked for and how it was handled by the archivists.

Usually the rule is one folder at a time from a given box, so the archivists give you something to mark the place in the box where it came from. Sometimes boxes have bundles of letters inside. You don’t know until you open it. Bound volumes like the one in the picture above need book rests to support their spines, so archives stock various kinds of cushions for that purpose.

There’s a common misperception that readers have to wear white gloves to hold old documents. In fact, the opposite is true: archivists prefer that you don’t wear white gloves when handling documents. Gloves can be just as dirty as fingers, and you lose a lot of dexterity when you wear them. That makes it more likely that you’ll accidentally tear the corner of a page. The only exception is for photographs—gloves are usually required for those.

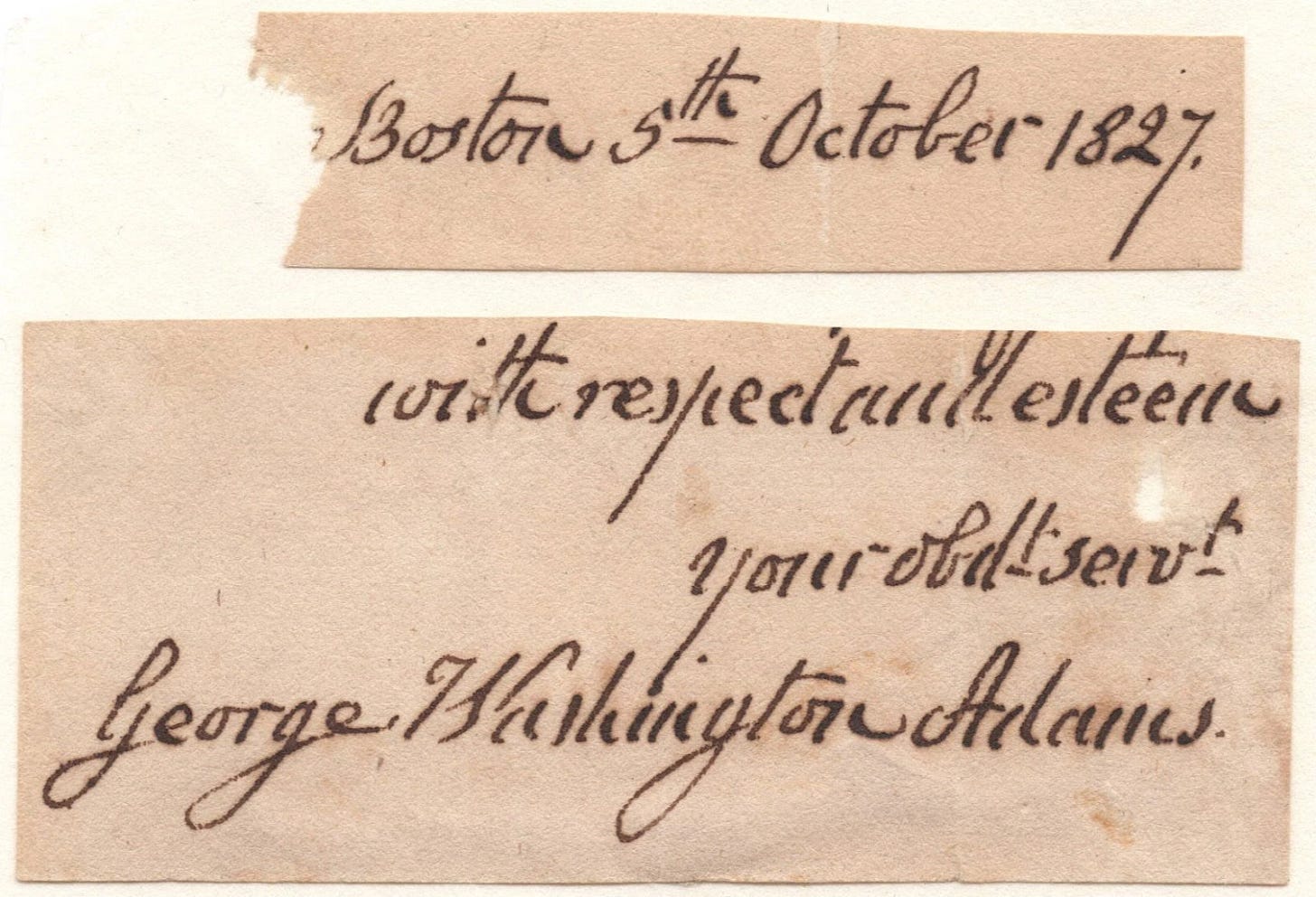

Archivists worry that you’re damaging the documents, of course, but what they’re really worried about is that you’ll try to remove documents or cut out valuable parts of them. eBay is full of autographs from famous people—many of those were removed from archival documents using x-acto knives.

Don’t buy them! Be suspicious also of maps that used to be in books. There’s real money in this dirty business, which is why the British Library and Kew, for example, issue clear plastic bags to hold your stuff. Most archives also make you open your laptop when exiting to make sure you didn’t stick a document between the keyboard and screen.

What do you find in archives?

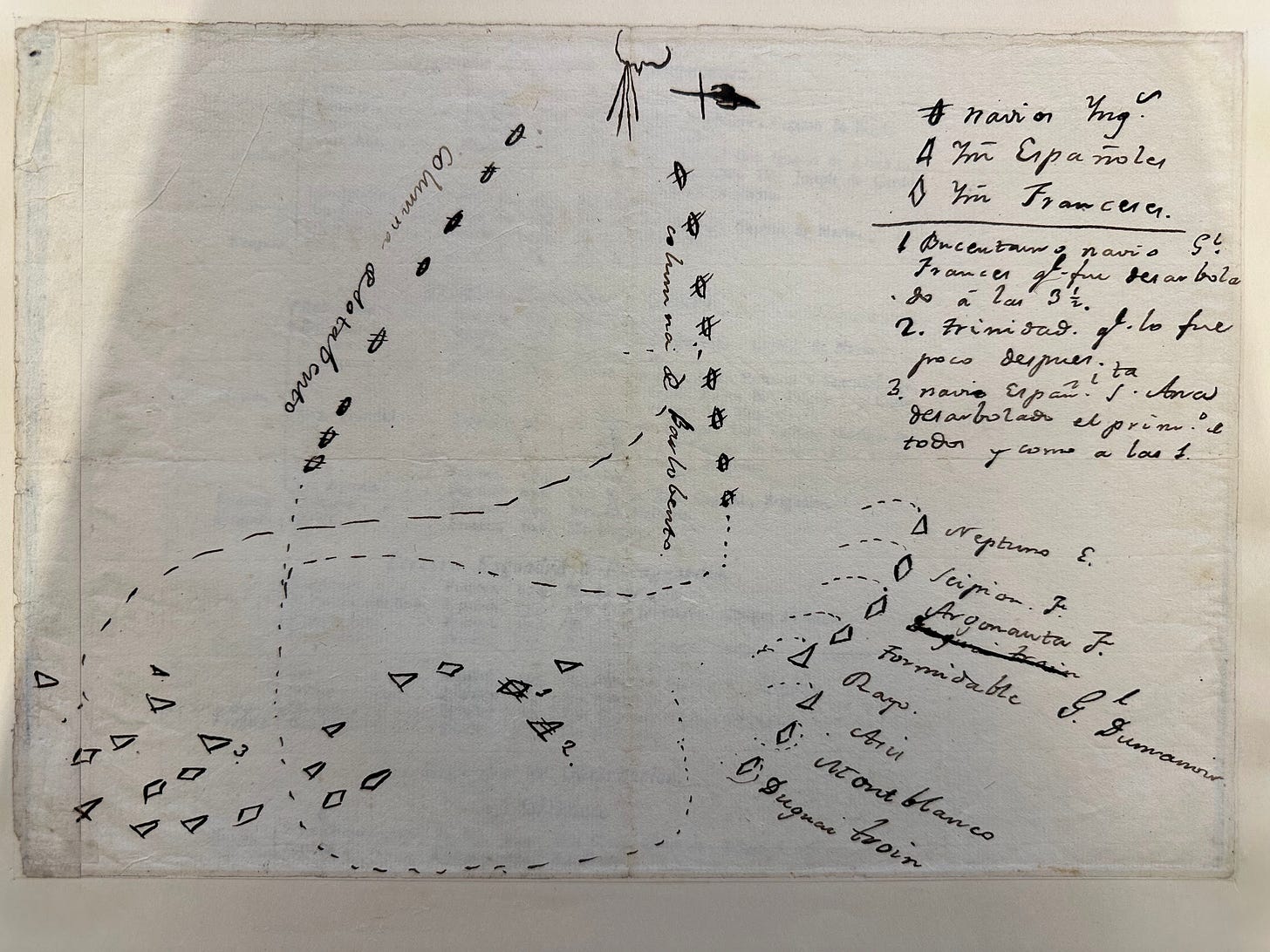

So many weird and wonderful and ordinary and moving and annoying things. This post is long enough, and I’ve talked about my archival discoveries elsewhere on this blog, so I’ll wrap it up with one cool find. Here’s a sketch of the Battle of Trafalgar by a Spanish participant. It wasn’t what I was looking for when I got to the archives, but sometimes the best finds are the ones that happen by accident:

I’ve been reliably informed by an archivist that archives is the correct singular noun.

I’m confused by this, to be honest, since I think there are only two reasons to visit an archives: 1) to conduct research; 2) to steal stuff. But presumably you wouldn’t tell them, “I’m here to steal stuff.”

Private family archives sometimes care that you’re not trying to make their ancestor look bad, so they can be tricky. I don’t have much experience with this kind, though.

Again, though, this has always struck me as needlessly annoying. I guess it’s so they can hunt you down if you steal something.

I’m told that once upon a time, digital cameras weren’t a thing, which meant (*shudder*) that you had to take notes on the spot with a pencil! How did anyone write anything last century?!

Nice post. I used one private archive that charged me 20 Deutschmarks per day, plus photocopies at 1DM per five pages. But that was in the last century.

It pays to make absolutely certain you have an appointment. The archivists need time to process all these masses of paper, so they may ask, “please don’t ask us to pull documents on Wednesday mornings. You can use what you already have until after lunch.” Without their processing, and reshelving, no one could find anything.

In the good/bad old days, you would ask (beg?) archivists to make photocopies of your material, often at extortionate rates. Some places required you to identify the archive on each item. I remember this as being a particularly hard time suck for poor grad students seeking to get as much material digested as possible in a short period of time.