Students in the graduate certificate program I co-direct are embarking on their year-long research projects this week. I’m leading a project design workshop for them tomorrow, and I thought I would share some of my notes with you in the hopes that you might give me some feedback or that you might find them useful.

The parameters of the research project are:

In consultation with a faculty advisor, research a subject in maritime or naval history, from any era.

Write an article-length (6,000-16,000 words) essay “of publishable quality.”

I hope this post might be of more general interest because to get master’s students pointed in the right direction, I have to explain to them why I do what I do and how I do it. A large part of my job is to do exactly what they are doing: research and write articles of 6,000 to 16,000 words for publication. Also, I hope you see some of the themes from my posts on The Horrible Peace reflected in what follows.

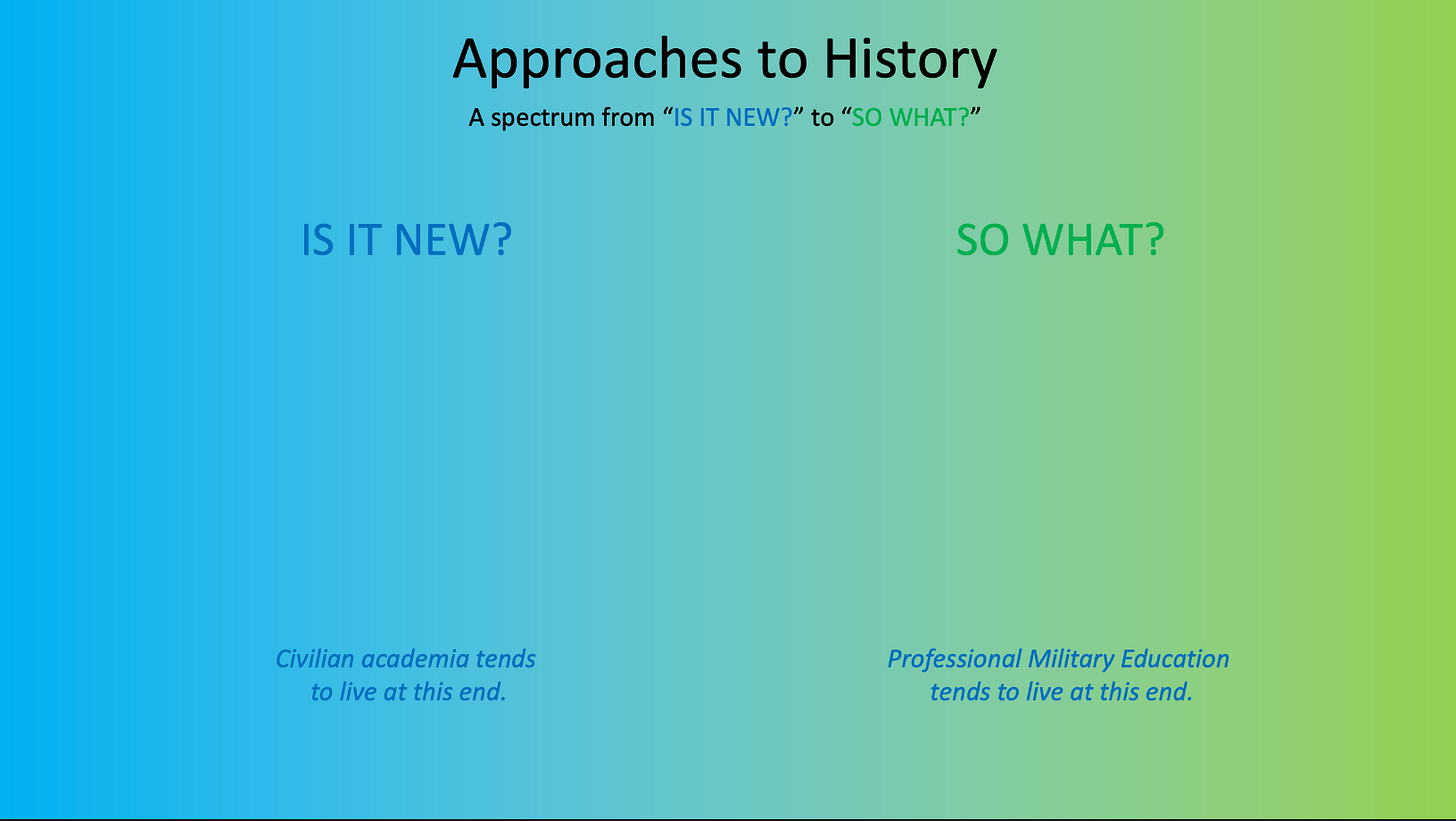

In the workshop, I start with a general, exaggerated observation, which is that they should design their projects to address at least one of the following two questions:

Is it new?

So what?

Ideally, I say, the project should address both.

I associate the first question with Nicholas Rodger, my doctoral supervisor. He speaks and/or reads more than half a dozen languages, and he constantly pushes his students to do the same. It was not uncommon to leave a supervision with him with a stack of books in Swedish. Whether I could read them wasn’t the point—he figures that any aspiring scholar should be able to make headway in almost any foreign language. He wants his students to incorporate non-Anglophone perspectives and to situate their projects in relation to everything, in any language, that has been written about the subject.

Most of his students, myself very much included, fail to meet his exacting standards, but that doesn’t mean he’s wrong. For a historian embarking on a new project, what’s the use in repeating what has already been said? And are you sure that the English-language perspective you’re getting encompasses all of the perspectives relevant to your subject?

I associate the second question with Paul Kennedy, who asked me exactly that question in response to a presentation I gave. What he meant was, Why should we, today, in this place, care about what you’re researching? Not all history is policy-relevant, as I’ll show below, but that’s where Paul’s intellectual interests have taken him. The last chapter of his most famous book, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, applied his analysis of the economic underpinnings of great power politics to the contemporary (i.e. 1987ish) world. What he got right and what he got wrong isn’t the point—the point is that he was called in front of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee to defend his historically-informed argument that the U.S. was in relative decline.

For any new project, I tell students that it’s worth asking what that project’s relationship is to issues of contemporary concern. Since most of my students are mid-career military professionals, this comes naturally to them. They want history to be useful. It’s more common to have to pull them back from looking for directly-applicable “lessons of history,” about which I hope to say more in a future post.

Not every research project will answer both questions equally, nor is it always appropriate to ask both questions. But I hope that these two questions will provide students with some bright stars for navigation purposes.1

Historical Approaches

The next stage of the project design workshop involves my attempt at a taxonomy of research questions, using “is it new” and “so what” as the two endpoints on a historical approaches spectrum. I’m still tweaking it, and the full version of the slide gets very messy, but here’s my starting point:

Approaches include “hold up a mirror to the present,” “understand the human condition,” “explain how we got to the present,” “myth-busting,” “questions for policymakers,” and more.

The point of my taxonomy is to show students that some approaches to history tend to situate you towards the “is it new” end of the spectrum, while others tend to situate you towards the “so what” end. For example, if you’re studying how navies thought about their enemies in advance over the last four hundred years, and if you include a discussion of how the Chinese, Russian, and American navies are thinking about their enemies today, you would be on the “so what” side.2 That appears on the slide as “questions for policymakers.”

In contrast, if your historical research project analyses naval heroes in mid-Victorian family magazines, you are likely to be towards the “is it new” end. That appears on the slide as “understand the past on its terms.”

Both projects incorporate the opposite question: we hope that the chapters on navies thinking about their enemies are new as well as policy-relevant, and the historian of mid-Victorian naval heroism is adding to our understanding of identity, popular culture, and heroism. But the point is that each approach emphasizes one of the two questions more than the other.

Which end of the spectrum your research project is on matters because it’s what gives it the vector that it needs for publication. It doesn’t make sense to put questions for policymakers in an academic journal that nobody reads.3 Similarly, a policy journal is not going to care what your research reveals about the human condition, but an academic journal will care that you’ve done something new. The vector you choose is also how you’re going to sell it to the editors and the peer reviewers. If you don’t tell them that you’re saying something new, or that you’re saying something relevant, they might not infer that from your meticulously researched text. I encourage students, therefore, to be bold in presenting the fruits of their research, and these two questions can help them do that.

I also want to remind them that this spectrum is entirely made up in my head, by me, and they should not reference it. I’ve been burned before by students assuming that this spectrum has some sort of authority behind it. Nope, just me. The point of it is simply to give them some questions to think about, and to think, in a meta-cognitive sort of way, about why they are asking the questions that they are asking.

I look forward to any feedback you might have!

To be clear, I don’t mean to say that Paul Kennedy never cares about whether something is new or that Nicholas Rodger never cares about the “so what” value of historical research. All historians care about both, and many other things too, depending on the project.

That’s the subject of a book that Paul Kennedy and I are editing, due out next year—watch this space.

But I repeat myself.

I like this, not least because I’ve long told students that their work should factor in the “so what” approach.

You also can push the “what’s new” idea through the innovative use of old sources or the discovery of new ones