Master and Commander - Author's Note (1)

Sources

O’Brian begins the series defensively, with an appeal to his own expertise. He starts not with a concert in Port Mahon (more on that soon) but rather with an author’s note. He says that what you are about to read will seem wildly improbable, but in fact, he has gone “straight to the source for the fighting in this book.”

Nothing gets a historian more excited than when you tell him or her about your sources. So, what were O’Brian’s sources?

“The pages of Beatson, James, and the Naval Chronicle, the Admiralty papers in the Public Record Office, the biographies in Marshall and O’Byrne.”

Let’s take those one at a time.

Beatson is the most unusual of the bunch. Robert Beatson was a Scottish army officer and author of the six-volume Naval and Military Memoirs of Great Britain, which covers the period 1727 to 1783. Beatson has fallen off most historians’ radars because he is as old fashioned as can be—he’s a chronicler of events, most of which took place in his lifetime. I have to confess that I had not really looked at Beatson before I started this blog. By all accounts Beatson was careful and there’s no obvious reason to distrust what he has to say, but he would not be my first stop for narratives of naval actions. We’re off to a strange start!

James is William James, and he’s more well-known—he probably would be my first stop. British-born and trained as a lawyer, he was in the United States when the War of 1812 started. He escaped to Halifax in 1813, and he spent the rest of his career angry that the United States claimed to have won the War of 1812 and defeated the Royal Navy at sea. He decided to write a book to put the United States in its place, and eventually that project grew into a much larger one, The Naval History of Great Britain, covering 1793 to 1837 in six volumes. It’s obviously written by a lawyer: accurate in the details, but (as one critic puts it) “narrow, partisan, and devoid of any general historical awareness.”1 Novelists don’t need general historical awareness, though, and for details of small ship actions, James can’t be beat.

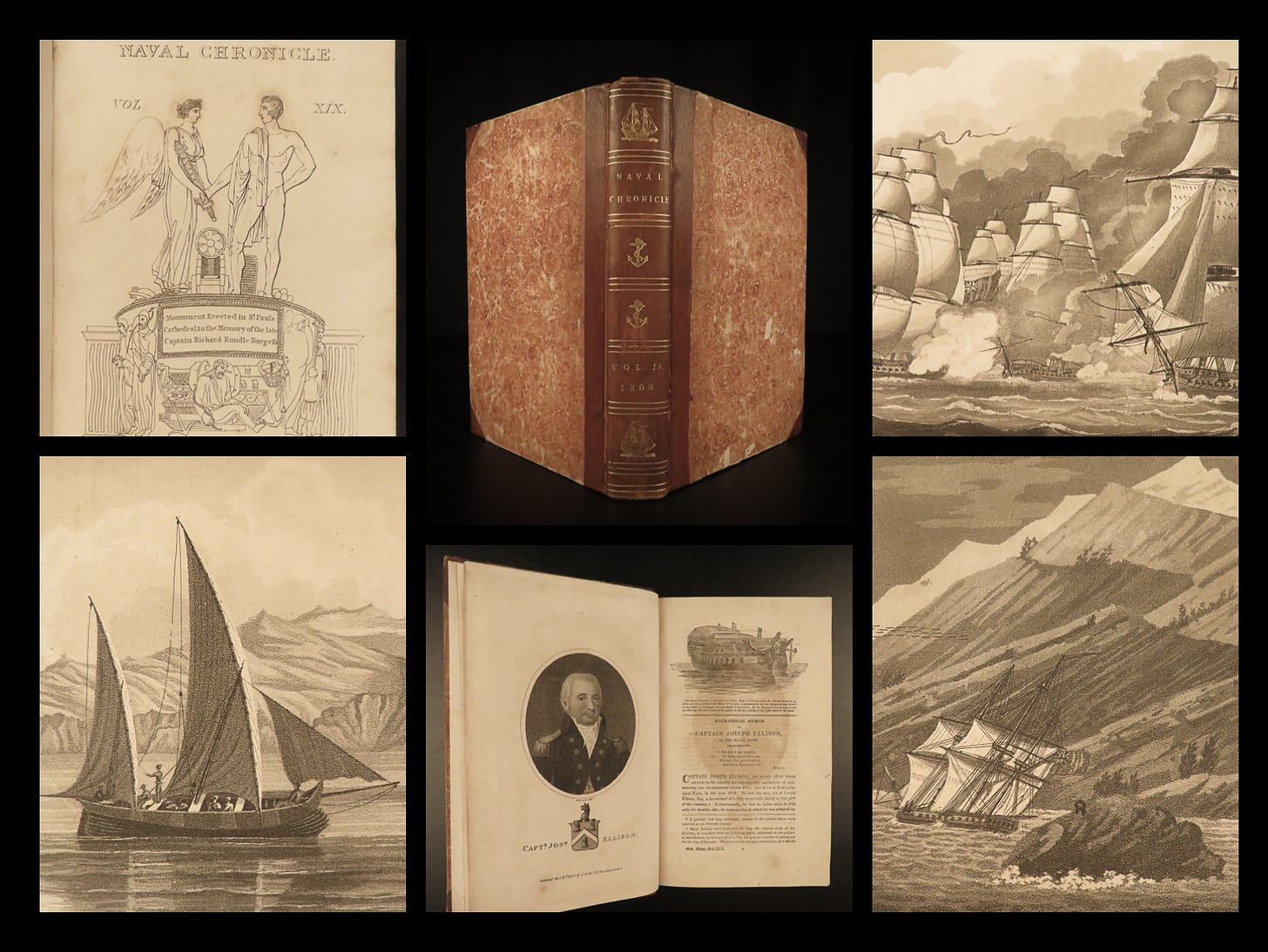

The Naval Chronicle was a periodical published between 1799 and 1818. It’s a rich source for a novelist, full of little snapshots of naval life. Any given issue would have debates about naval policy, biographies of senior officers, comings and goings of ships out of various ports, copies of letters from officers, and accounts of recent actions. In between, there were naval poems and illustrations. You can see a sample of it at the top of this post.

What O’Brian means by “the Admiralty Papers at the Public Record Office” becomes clear later in the note: “When I describe a fight I have log-books, official letters, contemporary accounts or the participants’ own memoirs to vouch for every exchange.” That’s the good stuff!

Though I do wonder sometimes about memoirs. Here’s what I said in my first book about the next two sources O’Brian listed, Marshall and O’Byrne:

John Marshall compiled a multivolume and multipart biographical dictionary of all living naval officers at the rank of commander and above during the 1820s. William O’Byrne included lieutenants in his thousand-page tome, but he was working in 1849. Both men solicited the biographies from the officers themselves, which explains why they were only interested in living officers.2

I wrote my first book in part to broaden our understanding of Nelson’s generation of naval officers beyond Marshall and O’Byrne, and I remain skeptical of sources that derive from officers’ own faulty and highly-motivated memories. But there are definitely some good sea stories in there!

And that’s the point: what O’Brian needed was raw material, and these sources provide them.

What’s missing

This exercise made me wonder about the sources that O’Brian doesn’t mention. Two themes that we’ll be exploring in this series are what parts of naval history O’Brian got wrong, and what parts he got more right than any historian bound by sources ever could.

Nowhere in the author’s note does O’Brian mention any histories that would help him understand how the Royal Navy as an institution worked—its administration, shore establishments, bureaucracy, etc. That, it turns out, is one of O’Brian’s great historical blind spots.

At the same time, O’Brian is also pretty thin on sources that would help him recreate everyday life aboard ship. It’s true that captain’s letters and logbooks can do that, but I can say from experience that you have to work very hard to get from those sources to what it was actually like aboard a given ship. You have to read between the lines and get lucky with the log entries, most of which just tell you the weather and what the “people” were occupied doing that day.

Here's a lively log entry—most of them aren’t full of this much action:

Some highlights, loosely transcribed: “The sloop makes 15 inches water an hour. … Saw several French fishing Boats come out of St. Vallery [Saint-Valery-sur-Somme] at 8. … Brought too & took a fishing boat. At 5 gave chace to several French fishing boats, fired several shot & took 2 of them, one of which run on board us & carried away [lots of things] … The fort fired several shot at us. … At noon three French fishing boats in Company.”3 That’s a busy day! But there’s no blood—I don’t mean casualties, I mean life.

O’Brian could take an entry like that and use his imagination in ways that I can’t as a historian, and, as the rest of this series will explore, the shipboard world that grew out of that imagination is probably his greatest historical accomplishment.

N.A.M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain, 1649–1815 (New York: W.W. Norton, 2004), 819.

Evan Wilson, A Social History of British Naval Officers, 1775–1815 (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2017), 227.

Admiralty: Captain’s Logs, ALBANY, June 14, 1760, TNA, ADM 51/22.

Having grown up on Hornblower, I find myself musing on the possibility that O'Brian saw that in some degree he was challenging the established master of the genre? By reputation, Forester had given the world the masterwork archetypes of 'age of sail' fiction. When I arrived in Washington DC to begin my government service, I was not surprised to learn that Management gurus had identified the Hornblower novels as an excellent example of how one advanced in an hierarchical organization by learning a new job position having mastered the duties one level below and beginning to look at the skills that would be needed for the next level up. Re O'Brian, I actually toured Mauritius's Napoleonic history using the novel "Mauritius Command" as my guide book!