Master and Commander - Dueling

To duel or not to duel

In the first scene, as Jack’s enthusiasm for the music bubbles over, “an elbow drove into his ribs and the sound shshsh hissed in his ear.” After the performance ends, Jack wonders whether he should escalate matters: “A nudge, a thrust of that kind, so vicious and deliberate, was very like a blow. Neither his personal temper nor his professional code could patiently suffer an affront: and what affront was graver than a blow?” On the next page, Jack fantasizes about beating Stephen to death with his chair.

Jack resists but then tells Stephen his name and where he’s staying; Stephen reciprocates. Exchanging that information was polite; it was also, both men knew, to enable Jack to challenge Stephen to a duel.

It’s worth restating just how poorly this relationship starts. In the first encounter between the two main characters—the two great friends around which the entire series pivots—O’Brian has them almost fight a duel in which one or both of them might have been killed.

Dueling is a recurring theme in the novel. Jack tells Stephen about a time when he challenged his commanding officer to a duel (“whether he might like to meet me elsewhere”) on page 138; the result is that Jack is reprimanded. On page 170, Dillon questions Jack’s courage, explaining that he cannot know for sure “without proof.” On page 181, Jack tries to get the Sophie to sea as quickly as possible so that Dillon doesn’t fight a duel (though it’s later revealed that he had). Et cetera.

I’ll leave the literary analysis there; from my historian’s perspective, the task is to explain why anyone in their right mind would ever think that fighting a duel was an effective way to resolve a dispute.

The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.

- L.P. Hartley

This post is in no way critical of O’Brian’s verisimilitude. He was correct to weave duels into his story because dueling and issues of honor really were important to British naval officers circa 1800. What I’m trying to do here is to provide some additional context.

To understand why officers dueled, we need to understand what honor meant for men like Jack and Stephen. Possessing honor entitled them to respect. It was at the heart of what it meant to be a gentleman, which, like honor, is another slippery term. A gentleman embodied the idealized male independence that was so highly valued in eighteenth-century Britain. Honor was a binary concept: either a gentleman had honor and was entitled to respect, or he did not have it and was therefore not a gentleman. Admiral Lord St. Vincent (1735–1823) summarized the issue in his typically sharp and gross way: “The honor of an officer may be compared to the chastity of a woman, and when once wounded may never be recovered.” Therefore, officers were willing to go to great lengths to defend their honor.

Physical courage was a crucial component of honor. It was not the only component of honor—keeping your word was another, as was engaging in valorous acts of self-sacrifice—but dueling was a way to settle disputes because it showed how much you were willing to risk for the sake of your honor. Competence as a duelist was not necessary. All that mattered was that you had risked your life.

Did risking death actually resolve the dispute? Of course not! These are emotionally-stunted men we’re talking about. The resolution mechanism here is absurd:

So long as one or both of us isn’t dead, it’s all good. Somehow.

I know as a historian I’m supposed to empathize with the people I study, but sometimes it’s important to take a step back and say: nope, sorry, that was stupid.

You might be surprised to learn that the British navy thought dueling was stupid too. Even though its officers valued their honor highly, and even though its officers were acutely sensitive to questions of gentility, the navy banned dueling. After all, it was liable to cost them officers. Lots of other people shared the navy’s opinion. The Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge proposed a ban on dueling in 1712 that Queen Anne thought was a good idea, though it didn’t pass. Evangelicals in the last quarter of the eighteenth century also said dueling was un-Christian.

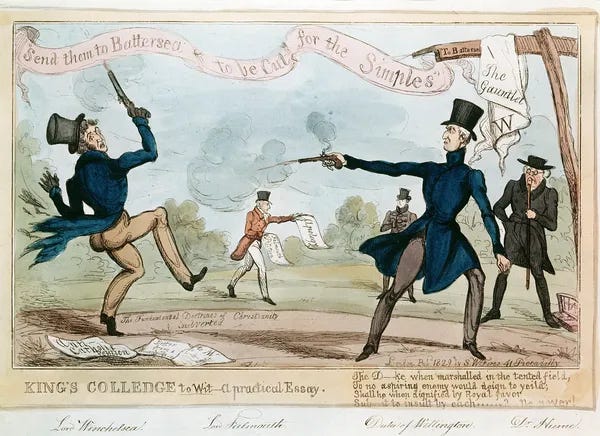

Yet officers still dueled; O’Brian has this spot on. Despite the navy’s ban, they waited until they could go ashore, and they did it surreptitiously. They cared about honor so much that they were willing not only to risk their lives, but also to suffer professional consequences for it. Dueling persisted, especially among military men, until the middle of the nineteenth century. The Duke of Wellington fought a duel in 1829. Why?

I spent an entire chapter of my first book answering that question, but let me provide an abridged version of the answer here:

First, guns made dueling safer (sort of). Dueling with swords is a terrible idea. You had to draw blood to consider the duel honorable. Blood means doctors. My personal worst nightmare is visiting an eighteenth-century doctor. No thank you. When pistols replaced swords as the primary dueling weapon in the second half of the eighteenth century, it actually made dueling less deadly. (Dillon duels with swords, but that was becoming much less fashionable by 1800.) Pistols were inaccurate, and firing at each other satisfied the honor criteria. You didn’t get extra honor credit depending on how accurate your shot was. Also, if one party thought the duel was stupid and did not want to harm the other, he could fire into the air. (He still had to stand there and receive fire, but that meant the chance of a death occurring diminished by half.) Getting shot was still very bad news, of course, but lowering the personal injury risk made men more likely to go out.

Another reason dueling persisted is that the mass mobilizations of the Napoleonic Wars flooded the countryside with trained, armed men who had internalized that they had to defend their honor with their life. Moreover, much of the actual experience of an officer (army and navy) mimicked dueling. When Jack took his ship into action, his job was to stand tall on the quarterdeck in his uniform and issue orders. He could not flinch when the shots started firing. Because standing still is boring, O’Brian often has Jack board the enemy ship, but boarding was actually pretty rare. The more common experience for officers in action was very much like a duel—standing still and receiving fire.

One young officer’s account of Trafalgar illustrates the behavior expected of an officer:

My eyes were horror struck at the bloody corpses around me, and my ears rang with the shrieks of the wounded and the moans of the dying. At this moment seeing that almost everyone was lying down, I was half disposed to follow the example, and several times stooped for the purpose,2 but … a certain monitor seemed to whisper, ‘Stand up and do not shrink from your duty’. Turning round, my much esteemed and gallant senior [Captain Hargood] fixed my attention; the serenity of his countenance and the composure with which he paced the deck, drove more than half my terrors away; and joining him I became somewhat infused with his spirit, which cheered me on to act the part3 it became me.4

My book spends a lot of time trying to understand the relationship between honor and duty,5 which is what originally causes the officer to stand up. It’s difficult to find officers speaking so directly about motivations and concepts, though. Honor was so central to their identities that they took it for granted—why bother explaining or discussing ideas that they knew everyone understood. My task was certainly not impossible, but I had to grasp at snippets and repurpose quotations that other historians had already found.

The tension between honor and duty is what destroys Dillon in Master and Commander. Honor is central to his relationship to the United Irishmen and to Jack; he’s also an excellent naval officer with professional ambitions. As a novelist, O’Brian is able to explore that tension with a depth and subtlety that makes me jealous.6 Dillon’s dilemmas will be a theme of a future post from my father the novelist. Informed historical imagination can illuminate otherwise difficult-to-access truths about the human experience, though as a credentialed historian I’m obligated to remind everyone that informed and imagination are doing a lot of work in that sentence.

AKA the “underpants gnomes” theory of conflict resolution.

Good idea!

Another interesting concept—the extent to which being a gentleman abiding by the honor code was a part that men played, as if on stage.

Quoted in R. Pietsch, ‘The Experiences and Weapons of War’, in Quintin Colville and James Davey, eds., Nelson, Navy & Nation: The Royal Navy and the British People, 1688–1815 (National Maritime Museum, 2013), 176.

Which is almost as fun to say in class as “seamen.”

When I was a small child, I learned that my father wrote fiction; I asked what fiction meant, and concluded: “Wait, so daddy writes lies?” My career was, uh, overdetermined.