Master and Commander - The United Irishmen

Some of the great "what-ifs" in British and Irish history

Historians have a complicated relationship with counterfactuals. By definition counterfactuals did not happen. That makes historians wary of using them, since historians are trained to gather and analyze evidence of what actually happened.1 However, an important role for historians is to show that the past was contingent—it did not have to happen exactly the way that it did. Humans have agency and chance plays a role in human affairs. Different choices, or different luck, could have created different versions of the past and therefore the present. Used judiciously, counterfactuals can help highlight key inflection points.2

With that throat-clearing out of the way, let’s look at some of the most significant counterfactuals in Irish and British history. The context here is of course Dillon and Maturin’s involvement with the United Irishmen, the consequences of which Dad covered in the last post. O’Brien makes his characters deal with the fallout of what actually happened—the rising of 1798 failed. But it’s worth stepping back to look not just at 1798 but the two years prior to it. There’s more to the story than just the United Irishmen, and in fact the rising of 1798 is the least contingent of the major events of those years.3

British imperial rule in Ireland relied on force and on the suppression of Catholicism and Irish nationalism. That made it an obvious point of weakness that Britain’s enemies could exploit. Support for the French Revolution and for the idea of a French invasion connected to an overthrow of British rule became widespread in Ireland in the 1790s. There were French-Irish contacts between radicals, and conspiracies involving aid from Paris abounded. Recognizing the danger in 1794, British authorities arrested or forced into exile leading United Irishmen like Wolfe Tone, but these actions just served to bring the French and Irish closer together.

That is essential context for three of the most remarkable episodes of the French Revolutionary Wars. It does not take much historical imagination to see how the years 1796 to 1798 could have gone differently for Britain and for Ireland. When Maturin and Dillon get drunk and wonder what might have been, they are on solid counterfactual ground.

1796: Bantry Bay

In December 1796, Wolfe Tone and the French General Louis Lazare Hoche left Brest at the head of a major amphibious expedition. They had 43 ships carrying 15,000 men, and they hoped to land in southwest Ireland. Readers familiar with the western approaches to the English Channel at that time of year might be able to guess what happened: the weather was so terrible that even though they made it all the way into Bantry Bay, they were unable to put the troops ashore. The expedition returned to France, defeated by the storms.

You might also note that they were not defeated by the British. In fact, Wolfe Tone wrote in his journal, “I am utterly astonished that we did not see a single English ship of war, going nor coming back.” The Royal Navy was missing in action, sheltering from the storms at Spithead, halfway up the Channel. They knew that the French had sailed, but they did not know if they had landed or even how big the expedition was. The first British ships arrived in Bantry Bay on January 7 after the French had already abandoned the mission.

So that’s the first counterfactual: what if the Bantry Bay expedition had managed to get ashore? 15,000 men would have had a good chance of success, especially if they had been joined by a popular uprising against British rule.

1797: The Great Mutinies

The second counterfactual concerns the Great Mutinies of 1797. Sailors in the Channel Fleet—the fleet responsible for preventing invasion—mutinied, demanding a pay increase and other improvements to their working conditions. (It had been a century since their last pay raise, for example, so there were certainly good reasons for them to complain!) The mutiny spread to ships at the Nore, an anchorage at the mouth of the Thames, and there were related mutinies at Plymouth and elsewhere in the Empire. British naval operations in the English Channel were seriously compromised from the onset of the mutinies in April until their eventual suppression in June.

What if the French and Irish had managed to invade during the mutinies? Following the failure at Bantry Bay, Wolfe Tone went to the Batavian Republic, which was the name of the French Revolutionary satellite state set up in the Netherlands. He put together a new expedition of twelve ships of the line, thirty-nine smaller warships, twenty-eight transports and 15,000 soldiers, all destined for Ireland. The plan was to sail north around Scotland—given the prevailing winds, that’s not as crazy as it sounds. On July 10, with the British still reeling from the mutinies and unsure whether their sailors would weigh anchor, the troops were embarked. But the wind did not cooperate, and supplies began to run low. Eventually the troops were disembarked and paid off, with nothing having come of the plans.

Early in the Spithead mutinies, the sailors of the Channel Fleet promised to put to sea if the French did, so it is by no means certain that an invasion of Ireland would have proceeded unopposed. But the mutinies clearly hampered the fleet’s capabilities and distracted it from its primary mission. The French simply weren’t prepared to take advantage of the opportunity.

1798: The Rising

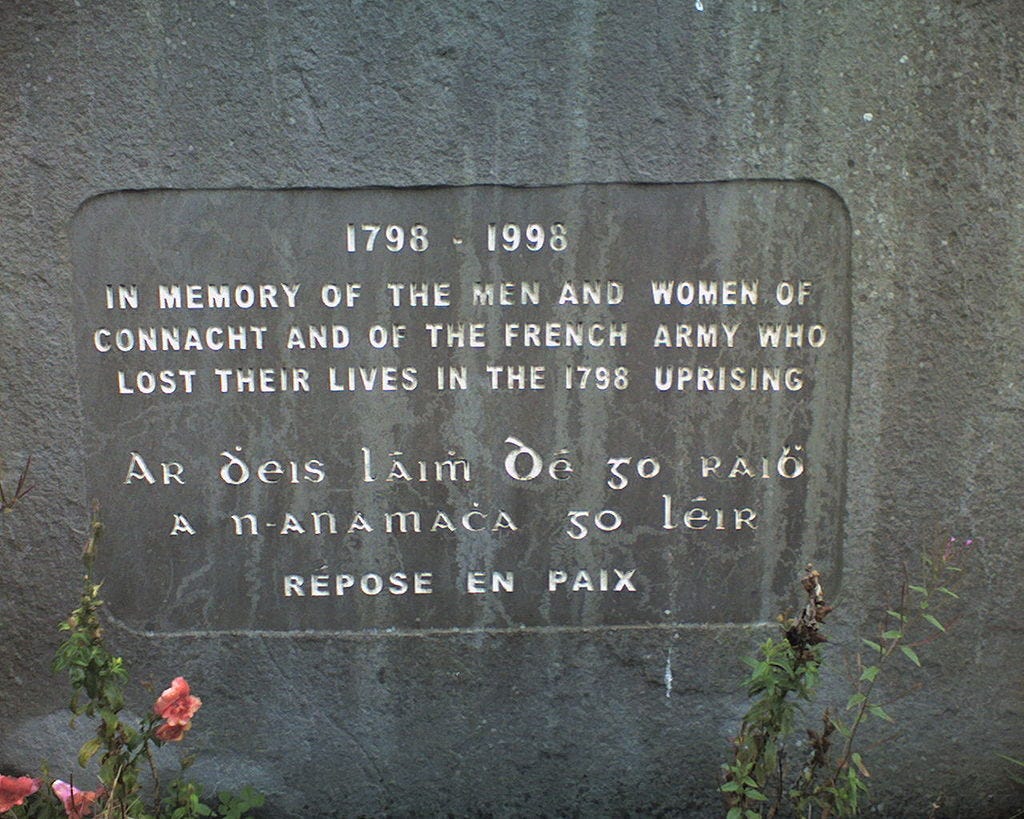

Bantry Bay and the Great Mutinies are plausible counterfactuals—there could have been different results. That’s not quite as true for the United Irishmen’s rising of 1798. At this point, the turmoil in Ireland and the repeated invasion attempts had alerted the British to the severity of the threat. British counterintelligence effectively infiltrated the rising before it could even get started. It is not for nothing that both Maturin and Dillon are exceptionally paranoid about being betrayed. The British took the sting out of the first attempt in May, and the United Irishmen were unable to coordinate effectively with the French. In the faint hope of inciting a second rising, the French sent a small expedition of 1,025 men well out into the Atlantic before turning east to land on the northwestern corner of the island at Killala. There was no real possibility of reinforcements, and the small force was quickly overwhelmed, surrendering in September.

British paranoia about the United Irishmen contributed to a long-standing myth that the organization had been responsible for inciting the Great Mutinies. As a forthcoming book by Callum Easton shows, there’s very little evidence that they had anything to do with the mutinies. But when you string the events of 1796, 1797, and 1798 together, you can see why the myth has proved so hard to kill. Even if they didn’t have anything to do with the mutinies, they should have! All that seems to have saved British rule in Ireland is the failure to coordinate French and Irish operations; paralyzing the Channel Fleet in the face of a French-backed expedition would have been a very effective tool for the United Irishmen.

As a historian, I am skeptical of saying anything more about the years 1796–1798 in Ireland than that it could easily have turned out differently. Whether a successful rebellion would have changed the course of the wars—nobody will ever know. Whether it would have prevented the Acts of Union that brought Ireland formally into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1801—probably, but beyond that, ¯\_(ツ)_/¯. Still, these counterfactuals can help us see more clearly that the trajectories of Irish and British history in those years were even more contingent than usual, and that small changes might have had outsized effects. That’s a useful thing for all of us to remember in these troubled times.

This has been another episode of Obvious Man!

There have been some attempts to theorize counterfactuals—to use them with more scholarly rigor. I don’t have the time or inclination to go into all that here. What I’m describing is, I think, how most historians think about counterfactuals most of the time.

I’m happy to share a PDF of the linked article if you’re curious.