I owe you a post about Jane Austen and the navy, but I’m too busy with other projects to do it justice. Hopefully I’ll get to it next week or the week after.

In the meantime, here’s the first post in an occasional series on eighteenth-century naval history based on common exchanges in my classes. Often, someone will mention Churchill’s line that the navy’s traditions were “rum, sodomy, and the lash.” That inevitably leads to questions about the extent to which each of those “traditions” was real. Since U.S. Navy ships today are dry, students are surprised to learn how much alcohol age-of-sail sailors consumed. Unsurprisingly, this is the kind of knowledge that students retain. So, as the term goes on, whenever students encounter a decision they can’t explain or an unusual event, they often ask, “Maybe they were drunk?”

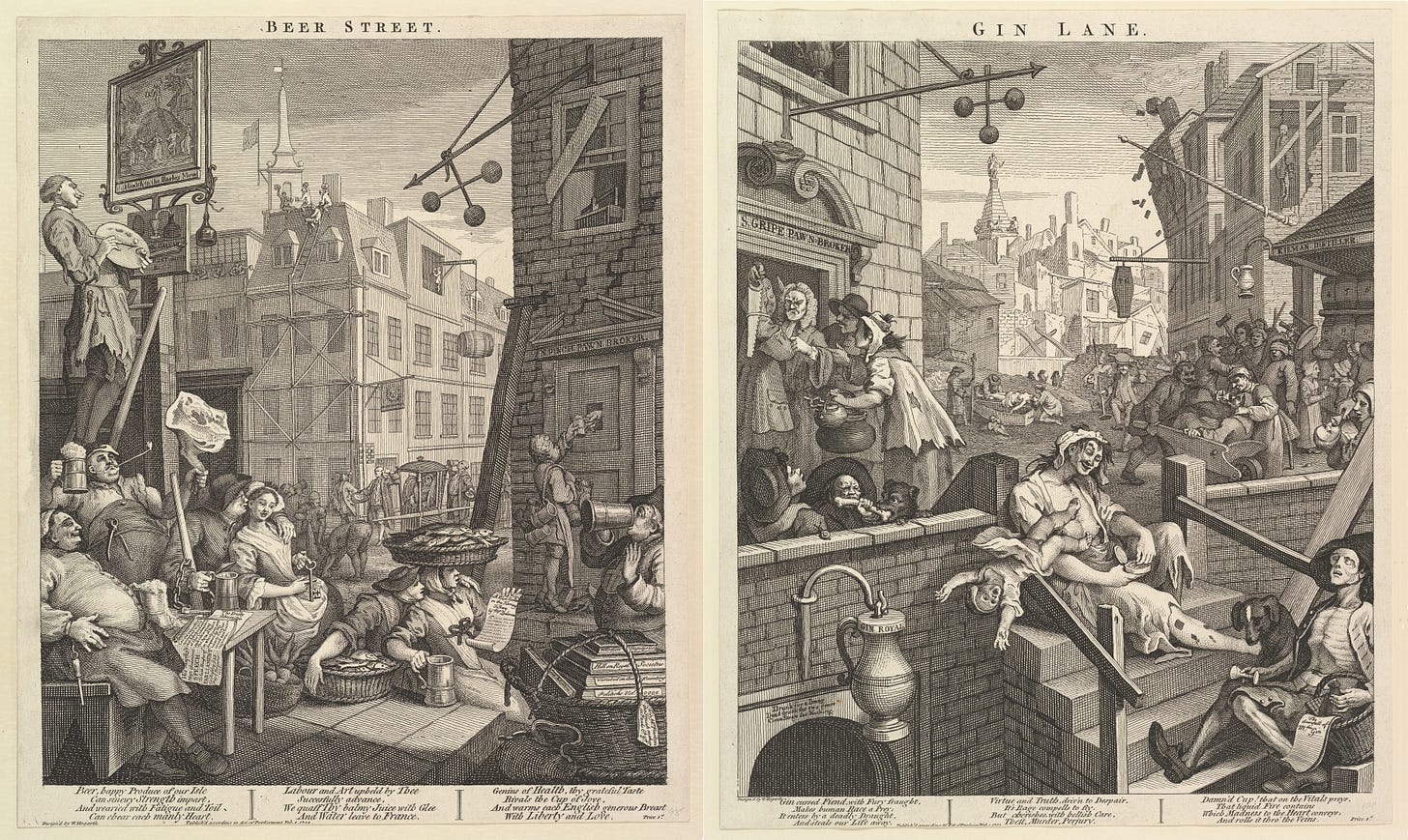

Now, I don’t want to overstate this. Sometimes alcohol consumption in the eighteenth century looks a lot worse than it was—beer, especially, was lower in alcohol content than we’re used to today. That’s partly why the folks on the left look so hearty:

But sometimes you come across accounts of alcohol consumption that make you wonder … maybe they were always drunk?

Here’s a letter that I encountered the other day that made me pause and ask that question. In 1780, the Duke of Leinster wanted Lord Gerald FitzGerald, one of his many sons, to go to sea, and he heard through his brother-in-law the Duke of Richmond that Captain John Jervis of the Foudroyant provided the best education for aspiring officers in the navy. Jervis also had the right kind of Whig politics, so Richmond made the arrangements for his nephew Gerald. Jervis was happy enough to take on a fourteen-year-old with an impeccable aristocratic pedigree.

Jervis probably had some regrets, though, when the boy showed up with a four-page letter from his father detailing exactly how he expected Jervis to treat him. Here’s an excerpt: “As he has never been far from home and is quite a child I should also like it as a great favor if you would put him under the direction of some proper person on board to regulate his studies and direct him as to the case and manners of things for a time till he can understand it himself.” Helicopter parents, it turns out, pre-date the invention of the helicopter.

The letter continues: “The only change I should fear for him would be leaving off wine, which he has always been accustomed to, and I should be very much obliged to you if you would order him to be supplied with a small quantity every day, never to exceed a pint of port.”

Let’s get one thing out of the way: fourteen-year-olds shouldn’t drink. But, ok, they did in the eighteenth century. A pint of port, though?

Well, maybe. The internet provides a huge range of answers for how many standard drinks are in a pint of port, ranging from 3.75 to 11.1 My back-of-the-envelope math came up with a little more than six.2 Leinster used that as a limit, which, thank goodness, but if that’s even something you feel the need to say, it should give you a sense of how much he expected Gerald to drink—per day.

For comparison, the naval rum ration was half a pint of rum per sailor per day, or between three and four standard drinks. It usually came in the form of grog (4:1 water to rum), which diluted it but didn’t change the underlying alcohol content. If rum wasn’t available, sailors got a pint of (non-fortified) wine or a gallon of beer, both of which also equate to between three and four standard drinks.

Sailors ashore had and have a well-earned reputation for excess, partly driven by the contrast between the regimented world of life at sea and the endless possibilities a young person with cash in their pocket can imagine in a port town. At sea in the eighteenth century, officers regularly punished sailors for drunkenness, but that was usually because the sailors had shared their grog rations with each other, snuck alcohol aboard, or managed to break into the ship’s stores.

The bottom line is that the amount of alcohol consumed daily on HM Ships exceeded the current American Medical Association recommendation of up to two drinks per day, but it was not so egregious that they were always drunk. Sailors were heavy daily drinkers and it did them no long-term health favors.

On the other hand, officers in the wardroom, and midshipmen with access to money like the Duke of Leinster’s son, could easily break through from heavy drinking into … well, whatever it is you choose to call a fourteen-year-old who has “always been accustomed to” wine and has to limit himself to a pint of port.

Here’s a source for 3.75; here’s 11; and the Google AI answer is 8.4.

A serving of port is about 3-4 imperial fluid ounces, and there are 20 imperial fluid ounces in an imperial pint. In US terms, a serving of port is about 3 US fluid ounces and there are 19 US fluid ounces in an imperial pint. That gives me five servings on the low end and nearly seven on the high end.

One of the classic retorts to the amount of alcohol consumed was to note how unhealthy was the water! There is also a question in my mind as to how much was burned off by the physical labor demanded of seamen and officers at sea.