I had the privilege of editing a forum in the International Journal of Maritime History on “Navies in the West Indies in the Age of Sail.” The final product will appear sometime in early 2024, but it’s on my mind because I just sent back the proofs of my introduction. In this post, I’m going to share a little of what I wrote because I tried to do something a little different. In a future post, I might share some thoughts on the process of getting the forum organized, edited, and published.

The forum consists of four essays, each on different aspects of navies in the Caribbean in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The authors are all brilliant: Ryan Mewett, Cori Convertito, S.A. Cavell, and Douglas Hamilton. They cover topics like the influence of mosquito-borne diseases on naval operations and the Royal Navy’s role in encouraging and also suppressing the slave trade. My job was to shepherd the projects to the journal, write an introduction to the forum, and then get out of their way.

When I sat down to write the introduction, I saw three possibilities. I could provide a potted summary of each article and draw connections among them. That seemed boring, though, and in any case, each article begins with an abstract. I wouldn’t be adding much value beyond the connections (I knew I needed to do some of that).

Another possibility was to reflect on the state of historical research on the topic, drawing on my extensive engagement with it over many years of writing books and articles. The problem with that approach, I realized quickly, is that I am not equipped to do that. I am not an expert on the West Indies! But that didn’t seem like a good reason to give up. After all, I’m a white man—when has not knowing what we’re doing ever stopped us? In any case, the four authors and the journal were depending on me.

That left one possibility: cover the basics. I decided to take the term “introduction” literally. One nice unintended consequence of doing that is that the result is a piece that I think could be read by an audience beyond the typical reader of the International Journal of Maritime History.

Below the share button (Which you should use! Tell your friends!) you’ll find the beginning of my introduction, which I tried to write as un-academically as possible. There were limits to this approach, of course: I was introducing an academic forum in an academic journal. But this isn’t my first academic article, so I thought I might take a few (minor) risks. I look forward to your thoughts on how I did.

Sugar and Navies in the Age of Sail

In 1999, the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich opened a new permanent exhibition called ‘Trade and Empire’. In a prominent display, a gentlewoman dressed in Regency style sat at a table, sipping tea. Next to her was a bowl of sugar, and under the table, a Black hand reached through the grating of a slave ship, pleading for freedom.1 This juxtaposition was an effective, albeit short-lived, way to encourage members of the public to contemplate an uncomfortable truth. At the turn of the nineteenth century, table sugar was not just glucose and fructose: it had many more ingredients. Enslaved labour was obviously the ingredient that the National Maritime Museum chose to emphasize, but there were others as well. To frame this forum on navies operating in the West Indies in the age of sail, let us go back to the basics. What were the ‘ingredients’ in that bowl of sugar? And where were navies on that list? Answering these questions, it is hoped, provides background and context for the contributors’ essays, none of which deals directly with sugar, to be clear. But any historical analysis of the West Indies in this period must acknowledge how the sugar economy functioned and why it mattered.

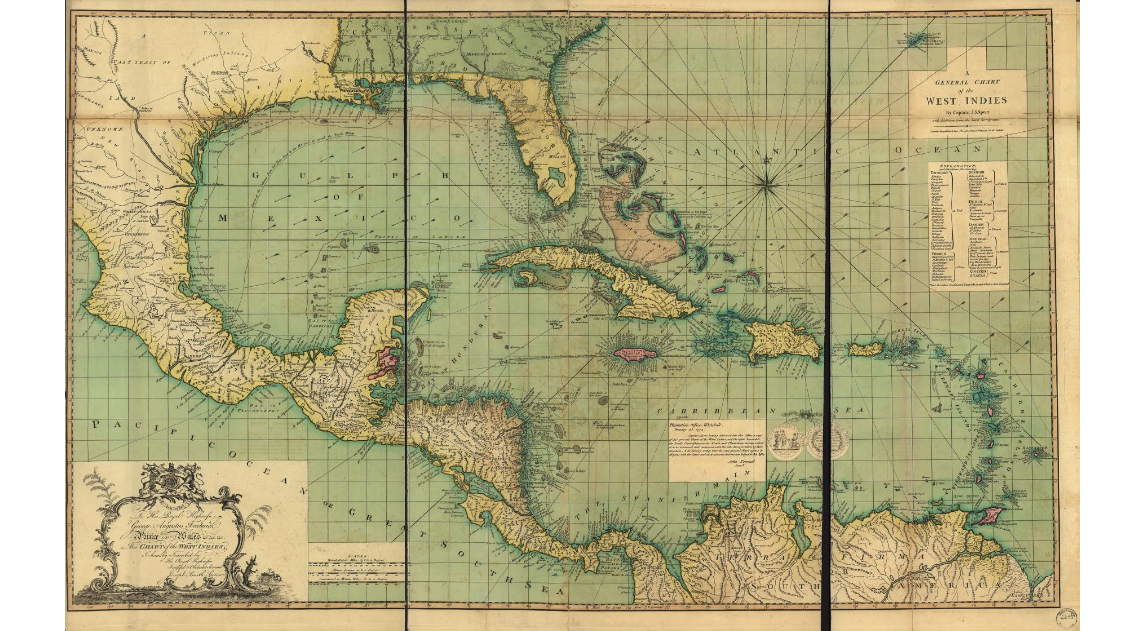

The first ingredient was wind. Why did sugar come from the West Indies, and not from some other region suitable for sugarcane cultivation? One important reason was that northern Europeans failed to find precious metals in the West Indies and so followed the example of the Portuguese and Dutch in Brazil by cultivating sugar. But more fundamentally, the West Indies sat roughly at the midpoint of the great circle route of the North Atlantic. To be clear, this had nothing to do with its geodesic distance from any other places; rather, the West Indies were the catchment for ships traveling from Europe to North America. The clockwise circle of trade winds and currents in the North Atlantic meant that the fastest route from London to New York was via the Bahamas. On Christopher Columbus’s first voyage, he sailed southwest from Spain to the Canary Islands, then west across the ocean to make landfall in the Bahamas. It was the most northerly of his four crossings—he subsequently made landfall in the Windward Islands, Leeward Islands, and near Trinidad. Wind placed the West Indies at the centre of transatlantic navigation and therefore at the centre of transatlantic commerce.

Wind also shaped the internal geography of the West Indies. A voyage from Barbados to Jamaica was usually uncomplicated and quick. A return voyage, against the prevailing winds, was the opposite. One option was to beat into the wind through the Mona Passage between Hispaniola and Puerto Rico and out into the Atlantic before turning south. Another was to follow the wind west from Jamaica, then use the current to round Cape Corrientes on the western end of Cuba and beat up the northern coast through the Florida Strait. But that did little to get a ship closer to Barbados, and so in fact the fastest route from Jamaica to Barbados might in practice take a ship via the Windward Passage to New York or London first.2 As Douglas Hamilton notes in his article in this forum, square-rigged deep water sailing ships moved Europeans and Africans to the West Indies efficiently, but once there, the ships failed in the most basic task of knitting the islands together into a cohesive political and economic unit. Instead, indigenous technology in the form of sea-going canoes provided the most effective means of moving from island to island.

By the time the sugar appeared in the bowl in London, though, the indigenous peoples were largely gone. The second ingredient in sugar was smallpox. In the century after Columbus’s arrival, smallpox and other diseases almost wiped out the Amerindian communities in the region. Then, in the seventeenth century, the British and French conducted campaigns of extermination or expulsion against surviving Kalinago populations. Whereas indigenous cultures survived in Mexico and Peru in sufficient numbers to shape the colonial societies of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, in the West Indies, disease and violence caused indigenous populations to become nearly extinct. Among the reasons for the introduction of sugarcane into the West Indies was that land was easy to claim in the wake of this demographic catastrophe.3 As one survey has described the West Indies, ‘In the seventeenth century, on this tabula rasa, the dynamic of early capitalist production for the world market then created new kinds of society consisting wholly of nonindigenous outsiders’.4

The outsiders came because of money, the third ingredient in sugar. Sugar exemplified a proto-capitalist commodity. It was produced for a global market by a globally linked system of labour and distribution. Demand for sugar in Europe and North America drove imperial activities in the West Indies. Planters worked hard to grow the market as well, and they successfully increased demand for colonial products, especially sugar.5 Demand was particularly high in Britain, which by the eighteenth century was a full-fledged consumer society in which purchasing power extended beyond a tiny elite.6 Enthusiasm for consuming sugar was matched only by planters’ enthusiasm for making money from its production. Planters maximized production to meet that demand while minimizing moral and ecological concerns.

Ecological concerns could not be entirely ignored, however, because the requirements of sugar production left the islands and their inhabitants devoid of other sources of calories. The unrelenting logic of capitalism meant that all the incentives for planters pointed towards monoculture and agribusiness on as large a scale as possible. The profits could be used to pay for food imports. This system—sugar out, food in—was fundamental to the imperial, commercial, and social history of the West Indies. Food for the enslaved laborers was the fourth ingredient in sugar—the fuel that powered slavery’s horrors.

Where each empire sourced its calories varied, but the consequences of that supply chain failing were always severe and sometimes unexpected. During the Seven Years War, for example, French planters on San Domingue (Haiti) struggled to get food to their island amid the disruptions of the naval campaigns. In these difficult conditions, they also grew increasingly alarmed by the spate of sudden deaths among livestock, enslaved people, and planters. They accused the Maroon leader François Mackandal of a systematic poisoning campaign. Executing Mackandal solved none of the planters’ problems and instead created a martyr for the later Haitian Revolution. In fact, the cause of the deaths was anthrax, pulled up through the roots of grasses by starving animals. Examples of island food supply chains being disrupted can be found in all the major eighteenth century wars.7

Clear-cutting islands to plant sugarcane and fuel the sugar mills had additional unintended consequences beyond food insecurity. Sugar transformed the ecology of the Caribbean basin. Rats overwhelmed native species of birds and monkeys. Flash floods became more common and more dangerous. Soil erosion decreased sugar yields, which spurred planters to import more enslaved labour. The combination of ecological change and increased transatlantic arrivals created the perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes. Those mosquitoes carried yellow fever and malaria, which made the West Indies a graveyard for those who had not before been exposed.8 Planters believed that West Africans possessed greater immunity against tropical diseases.9 Here was another incentive to increase the traffic in enslaved people, exacerbating the vicious cycle of slavery, disease, climate change, and profit. Yellow fever and malaria were two more ingredients in sugar.

European empires cultivated all these ingredients, especially the less savoury ones, because there was so much money to be made from sugar. That money spurred not only ecological transformations, the slave trade, and epidemics, but also competition. In every war, competing empires sought to capture sugar islands from their enemies. Sometimes, they kept their conquests at the peace, to exploit the sugar; other times, influenced by West India lobbies concerned about oversupply, they used the islands as bargaining chips to secure other strategically vital gains. Wars that started for other reasons in other places inevitably spread to the West Indies.

At last, then, we have arrived at the naval ingredient in the bowl of sugar. Wind, smallpox, money, food, slavery, yellow fever, malaria—and naval power…

It goes on from there for a bit to talk about how navies operated in the theater. It draws some connections among the four essays and returns to the NMM exhibit at the end. I’ll be sure to post a link to the forum when it’s published.

Unsurprisingly, the exhibit aroused a major controversy, and the Museum modified the exhibit to mollify some of its critics a few months after it opened.

N.A.M. Rodger, ‘Weather, Geography and Naval Power in the Age of Sail’, The Journal of Strategic Studies 22, nos. 2–3 (1999), pp. 191–93.

J.R. McNeill, Mosquito Empires: Ecology and War in the Greater Caribbean, 1620–1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), p. 16.

Jürgen Osterhammel, The Transformation of the World: A Global History of the Nineteenth Century, trans. Patrick Camiller (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2014), p. 132. (I stand by this paragraph, but I can see how Osterhammel’s use of the term “tabula rasa” might give the impression that Europeans claimed unused or vacant land. I want to re-emphasize the first couple of sentences: Europeans conducted a genocidal campaign in the islands before they turned to industrial sugarcane production.)

Sidney W. Mintz, Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (New York: Penguin, 1985); Carole Shammas, ‘The Revolutionary Impact of European Demand for Tropical Goods’, in The Early Modern Atlantic Economy, eds. John J. McCusker and Kenneth Morgan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), pp. 163–85.

Neil McKendrick, John Brewer, and J.H. Plumb, The Birth of a Consumer Society: The Commercialization of Eighteenth-Century England (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1982).

John Garrigus, A Secret Among the Blacks: Slave Resistance Before the Haitian Revolution (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2023); Richard B. Sheridan, ‘The Crisis of Slave Subsistence in the British West Indies during and after the American Revolution’, William and Mary Quarterly 33, no. 4 (Oct. 1976), pp. 615–41.

McNeill, Mosquito Empires, pp. 1–32.

Mariola Espinosa, ‘The Question of Racial Immunity to Yellow Fever in History and Historiography’, Social Science History 38, nos. 3–4 (2014): 437–53.