Violence without Guns

Clearing mass protests, then and now

Adam Tooze’s recent post on the protests at Columbia is worth your time:

He makes the point that guns freeze people, but clubs and riot gear encourage movement. Clashes between unarmed civilians and the forces of the state become a writhing mass of kinetic energy, of momentum, and of sound. If the primary weapon being wielded is human muscle and clubs, then the violence becomes much more personal and physical than it would be if two sides exchanged gunfire.

It’s also much less deadly, for which we should all be thankful.

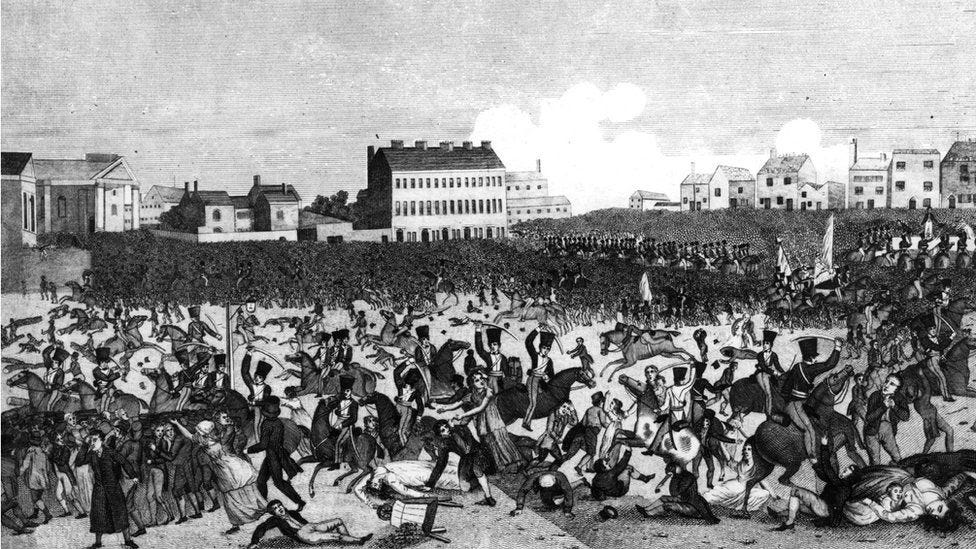

But his insight about the noise and the physicality and the nature of violence without guns made me go back and re-read some of the accounts of mass protest that I read while researching The Horrible Peace. I was struck by these passages in particular from the most famous and consequential of the post-1815 riots, Peterloo:

An officer and some very few others then advanced rather in front of the troop, formed, as I before said, in much disorder and with scarcely the semblance of line, their sabres glistened in the air, and on they went, direct for the hustings. At first, i.e., for a very few paces, their movement was not rapid, and there was some show of an attempt to follow their officer in regular succession, five or six abreast; but … they soon increased their speed, and with a zeal and ardor which might naturally be expected from men acting with delegated power against a foe by whom it is understood they had long been insulted with taunts of cowardice, continued their course, seeming individually to vie with each other which should be first.

As the yeomanry crashed into the crowd, they started wildly hacking away with their sabres, causing hundreds of injuries and dozens of deaths.

A newspaper reporter standing off to the side reported what happened next:

I saw the cavalry charge forward sword in hand upon the multitude. I felt on the instant, as if my heart had leaped from its seat. The woeful cry of dismay sent forth on all sides, the awful rush of so vast a living mass, the piercing shrieks of the women, the deep moanings and execrations of the men, the confusion—horrid confusion, are indescribable. I was carried forward almost off my feet.1

It is often desirable to be part of a crowd—at a sporting event, or a concert, or a peaceful protest. But one of the through-lines between Tooze’s account of his experience at Columbia and historical protests is how quickly the positive energy of a crowd can turn, and how dangerous a crowd feels for those in it when it is under stress.

The point of this post isn’t to ruminate on the state’s capacity for violence, or the differences among how the police are armed, or to speculate about another Kent State, or anything like that. The point is simply to reflect on what it feels like when the state turns its “blunt force” against a crowd. When it does so, it relies on the momentum equation: momentum equals mass times velocity. State forces want to get a lot of human mass moving in one direction at a great speed. That creates a different kind of terror in the target crowd than most of us think of when we think about state violence, but it’s a terror that has a long historical lineage.

The best book on Peterloo specifically is Robert Poole, Peterloo: The English Uprising (OUP, 2019).