Waterloo is the greatest victory in British history. The Duke of Wellington’s defeat of Napoleon on June 18, 1815, effectively ended the Napoleonic Wars and inaugurated the British century. Its significance was recognized immediately. Hugh banquets commemorated its anniversary every year, and there were monuments erected all around the country. All the participants, including the rank and file, received Waterloo medals.1 Fans of Jane Austen might also recognize this passage from Sanditon, which gives a sense of how the victory was received:

You will not think I have made a bad exchange when we reach Trafalgar House—which, by the by, I almost wish I had not named Trafalgar—for Waterloo is more the thing now.

Waterloo has been “the thing” for more than two centuries. One of the busiest train stations in London still bears the name, and it has become a common phrase: to “meet your Waterloo” is to come up against your ultimate obstacle and be defeated by it.

But the odd thing about Waterloo is that it should never have happened. More to the point, it was to a significant degree Britain’s fault that Britain had to fight the battle.

Before we get to all that, though, some housekeeping. If you haven’t already, hit that subscribe button:

I’ve also posted my first note on Substack Notes, linking to President Zelenskyy’s recent speech about rebuilding Ukraine after the war. I encourage you to join me on Notes by clicking here or finding the “Notes” tab in the Substack app. Its biggest selling point is that it’s a lot less Musky than Twitter, though to be honest, I’m worried that might not last.

Regardless, it comes free with your free subscription to War and Peace, so I thought I’d tell you about it. If I come across something relevant to a recent post, I’ll put it there.

The war so nice it ended twice

Waterloo didn’t need to happen because more than a year earlier, a Russian army had marched into Paris and forced Napoleon from the French throne.

That should have been that.

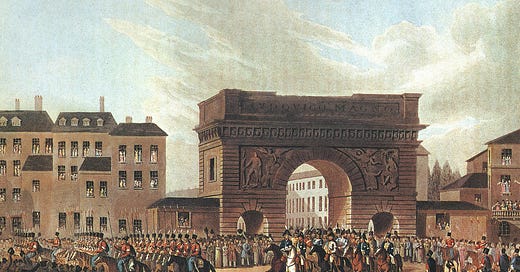

If you’re familiar with the Napoleonic Wars, Russians in Paris won’t surprise you—though it’s always good to get a reminder. If you’re not familiar with the story, it’s fantastic. Read Dominic Lieven’s Russia Against Napoleon for a detailed and engaging account of “The True Story of the Campaigns of War and Peace.” In short, the Russian army that had absorbed and then turned around Napoleon’s invasion in 1812 did not stop at the Russian border. Instead, it harried his forces all the way across central Europe through the bloody campaigns of 1813 and then, in 1814, into France. On March 31, Tsar Alexander I led a mostly Russian (but also Prussian and Austrian) army into Paris.

Lieven argues that the Russian role in the defeat of Napoleon has tended to be overlooked, even by some scholars. The weather gets too much credit for destroying the retreating French army, and the Russians too little. I wonder, as well, if historians writing in the context of the Cold War found the presence of 100,000 Russian troops in Paris uncomfortable to contemplate, and best skimmed over quickly.

The point is, the tsar’s arrival in Paris brought peace to Europe. From April 11 to May 30, a series of treaties and agreements removed Napoleon and replaced him with the Bourbon Louis XVIII, brother of the executed Louis XVI.

But of course that was not the end of the story.

It should have been! Instead, the Allies scored a series of own goals. The tsar, from his dominant position in the French capital, sent Napoleon into exile on the small Mediterranean island of Elba, and he gave him all the trappings of a head of state, including an army and a navy. Louis XVIII proved to be an inept and unpopular ruler, encouraging many in France to wonder if Napoleon’s return might be worth the associated risks.

The British, meanwhile, made mistakes at every level. Diplomatically, they let the tsar take responsibility for dealing with the turbulence in the French capital, which meant they had no say in the matter when the tsar decided on Elba. Strategically, they failed to station sufficient ships in the Mediterranean to keep Napoleon on the island. Operationally, they failed to issue clear instructions to the British commissioner on Elba about whether Napoleon was a prisoner or a head of state, and in any case, the commissioner preferred to spend time with his mistress on the Italian mainland. Tactically, the captain of the sloop tasked vaguely with keeping an eye on the island twice had easy opportunities to stop Napoleon’s departure, and twice he bungled it.

Napoleon barely needed to escape—it’s not even clear he was a prisoner. He returned to France in March 1815 to cheering crowds. He raised an army and marched north into Belgium, hoping to defeat the Allied armies in piecemeal before they could combine. Instead, he met his Waterloo (oof, sorry, please buy my book).

The tragedy at the heart of the great victory

All the Allied errors that led to Waterloo were identified as such at the time.2 Nobody thought Elba was a good idea, but it was too late to change the tsar’s mind. Nobody thought Louis XVIII knew what he was doing, but there didn’t seem to be a better option. And everyone assumed that the British were keeping Napoleon on Elba, except for the men responsible for doing just that.

It’s common when telling this story to focus on the missteps of Alexander and Louis, rather than the missteps of British officials.3 But we shouldn’t let the British off the hook. After all, 65,000 men died in the battle, and thousands more in the campaign.4 The great and costly British victory at Waterloo didn’t just rescue the Allies from Russian and Bourbon mistakes—it also rescued them from British mistakes.5

As is often the case, JMW Turner saw the costs of the battle more clearly than most (even if this painting is anything but clear):

Turner emphasized not the heroic drama of the fighting itself, but the horrible aftermath. The night after the battle, bodies pile on bodies, while Hougoumont farm (site of some of the bloodiest clashes during the battle) burns in the background. Turner displayed the painting alongside a line from Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage: “friend, foe, in one red burial blent.” Waterloo is best understood as a tragedy, and a deeply ironic and avoidable one at that.

If you liked this post, share it! And there’s more like this in the book.

For more on this, see Luke Reynolds’ book, Who Owned Waterloo?

If all the “should haves” have been bothering you, the linked article tackles the pitfalls of judging the actions of decision-makers in 1814 and 1815 with the benefit of hindsight. I’m happy to share a PDF.

I need to be careful here, but let me speculate a little about why historians haven’t paid enough attention to British mistakes:

Waterloo fits neatly into the world history narrative of British victory in 1815 leading to the Pax Britannica for the next ninety-nine years. Nearly blowing it (but not actually blowing it) in 1814–15 makes that narrative complicated.

Alexander and Louis made sufficient mistakes to explain Napoleon’s return—there’s no obvious need to dig deeper.

Napoleon is a natural (really, the natural) protagonist of his eponymous wars, and so it’s always tempting to shift the narrative to Elba in early 1815 to explain the drama of his “escape” from his perspective rather than from a British or Allied perspective.

The two greatest generals of the age meeting in a decisive battle is the stuff movies are made of. Waterloo is too useful a distillation of the complexities of the wars to spend time questioning why it happened, especially because it was the only time Wellington and Napoleon faced each other.

One of the points I make in the book is that fighting continued for five months after Waterloo, though from a grand strategic perspective, it was clear there was no viable path forward for Napoleon in France after June 18.

Calling it a British victory is also problematic. Just 36% of Wellington’s army was British; the majority of his soldiers were from modern-day Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Also, a Prussian army arrived late in the day to guarantee the Allied victory.