Why did convoys work?

The answer might surprise you (sorry)

Simple questions sometimes have surprisingly complicated answers, as any parent can tell you. Other times, though, simple questions have simple but unexpected answers. This is one of those.

It’s so unexpected that one of the greatest naval theorists got the answer wrong. In 1911, Julian Corbett looked at the long history of convoys at sea (which date back to antiquity) and argued in his seminal Some Principles of Maritime Strategy that convoys were now obsolete in the face of new technologies like steam power, radio communications, and mines. Concentrating ships into convoys in this new world made for target-rich environments, and a cruiser in 1911 could do a lot more damage to a convoy than a frigate could in 1811. Better, he argued, to use radio to route ships around attackers. Britain could also use its geographical position to keep German cruisers from getting near the valuable North Atlantic trade routes by mining inshore waters.1

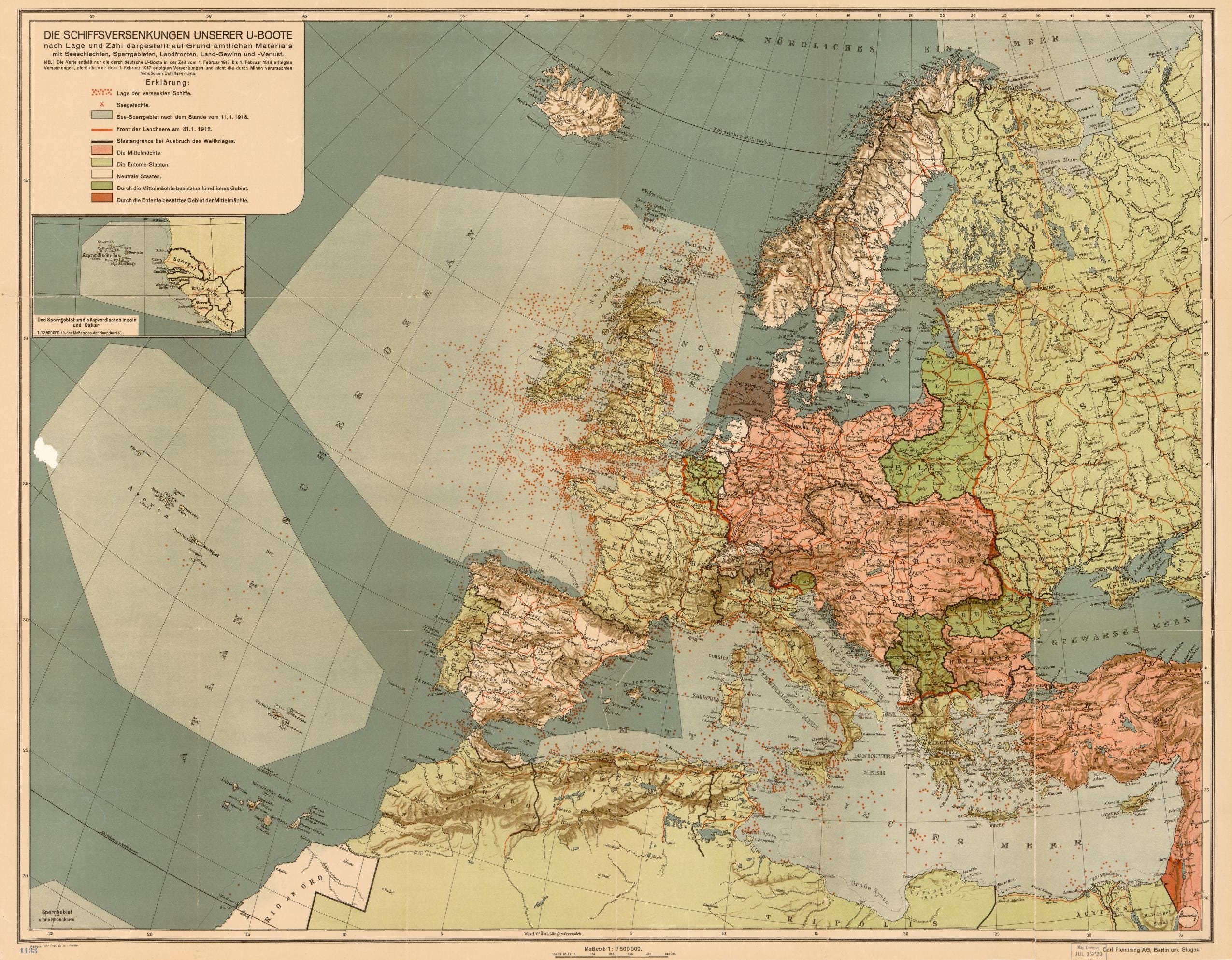

His analysis contributed to Britain’s belated introduction of convoys in the First World War. Lots of ships got sunk in the meantime, the majority of them by U-boats rather than cruisers. Look at all the little red dots on this map of U-boat sinkings in that war:

Corbett got lots of other things right, and in fact his analysis of why German surface raiders were unlikely to pose a major threat to commerce was spot-on. He could not have known that submarine technology would improve dramatically in the five years after Some Principles appeared. That failure is easily excusable; less excusable is his surprising failure to understand what made convoys effective at protecting trade.

We still read Some Principles at the Naval War College because in general it really is a heartbreaking work of staggering genius. I’m not here to bury Corbett or suggest that the failure of British trade protection in the First World War was entirely his fault. I’m just pointing out that even Corbett didn’t understand how convoys worked.

Back to Basics

So, let’s start with some definitions. A convoy is a group of ships sailing together for mutual protection. Often, though not always, convoys have naval escorts—armed ships tasked with herding the flock and defending it from attack. Here’s a British convoy entering the Baltic in the Napoleonic Wars:

In narrow seas like that pictured above, convoy escorts were why convoys worked. They protected the shipping. That’s probably the most common answer to “why did convoys work”—the escorts fought off the bad guys. But it turns out that in many (most?) other circumstances, escorts weren’t the primary reason why convoys worked. In fact, convoys could be effective without escorts at all!

With apologies for my low-budget illustrations, let’s imagine a SLOC (sea line of communication, which is a fancy name for a trade route) starting on the left and ending on the right. If there is no naval control of shipping on that SLOC—if there is no convoy system—then it would look like this, with each black line representing a ship and the blue circles representing the distance at which the ship can be seen:

In contrast, if there’s naval control of shipping, you can concentrate all the ships into one “detection area,” otherwise known as a convoy:

Convoys worked because they relied on one core component of the maritime domain: the ocean is really big. Convoys concentrated ships into one small area that made them hard to find. If you have fifty ships sailing independently, you have fifty different points to attack and fifty different points to defend. Moreover, each ship is visible from a certain distance; putting them all together didn’t increase that detection distance by much and it removed all the detection areas from elsewhere in the ocean.

For that reason, the British and Canadians instituted naval control of shipping—the convoy system—on the first day of the Second World War. They did not repeat the mistake they’d made in the First World War. And they were right to do so, as the Germans themselves admitted in their Handbook for submarine commanders, which said that convoys made the sea routes “desolate.” Even in the war’s early months, when U-boats generally felt confident operating close to the British Isles where traffic was more predictable and concentrated, convoys proved difficult to locate, particularly in bad weather. It was really hard to spot a convoy from the conning tower of a U-boat pitching and rolling in the North Atlantic.

If you want to read a lot more about convoys, U-boats, and the first few years of the Second World War, check out my article on the subject.

Combat was a part of convoy operations, but it was a secondary factor in their effectiveness. Through 1945, convoys also relied on the fact that even when concentrated, it was usually not possible for attackers to sink or capture all the ships in a convoy. There were more targets than torpedoes (again, usually).

Convoys also served as bait, luring attackers into a position in which escorts could engage them. If you put a convoy in the Western Approaches (the area where many of the sinkings are in the map above, north and south of Ireland), you didn’t need to go looking in the big ocean for little French privateers or German U-boats. They would come to you. That was what Alfred Thayer Mahan argued in his discussions of convoys: “The convoy system, when properly systematized and applied … will have more success as a defensive measure than hunting for individual marauders—a process which, even when most thoroughly planned, still resembles looking for a needle in a haystack.”2

That’s how convoys worked: they made detection more difficult; they relied on the difficulty that attacking forces had in carrying enough weapons to sink all the ships; and they brought attackers into a position where escorts could engage them.

I’ve written most of this post in the past tense because once again there seem to be good reasons to suspect that convoys are obsolete. Whereas Corbett thought that technology in 1911 had changed the balance of forces at sea mostly in favor of the defense, which made convoys unnecessary, today, technology seems to have changed the balance of forces in favor of the attacker. In a great-power maritime conflict today, no longer would the attacker be hunting for convoys from a submarine conning tower with a Mark 1 eyeball. Satellites and radar make finding ships on the ocean much easier now than it was eighty years ago. Moreover, putting a missile on a container ship today seems to be a lot easier than putting a torpedo in a tanker in 1942.

Nevertheless, there clearly needs to be some thought about how to protect shipping in a shooting war. It’s a core purpose of navies, and always has been. For most of the history of naval warfare, convoys have been the most effective form of commerce protection. That might not be the case any more, but we should at least understand why they worked.

Julian Corbett, Some Principles of Maritime Strategy (Longmans, Green, 1911), 258–71.

A.T. Mahan, The Influence of Sea Power on the French Revolution and Empire, 1793–1812, 4th edition (Sampson Low, 1892), 2:217.