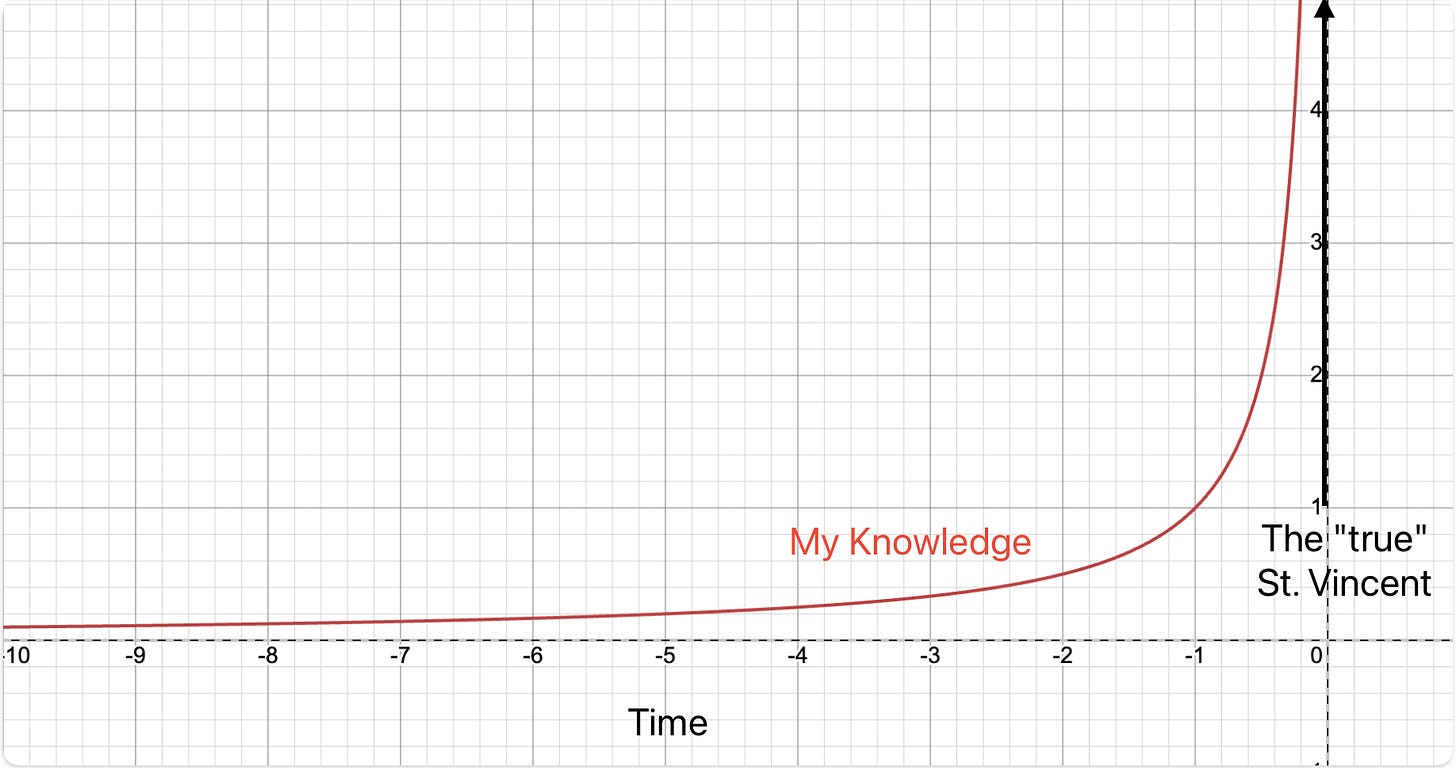

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the limits of my own knowledge. Writing a biography (in my case about the earl of St. Vincent) is an exercise in the asymptotic gathering of information. Like so:

That’s just science.1

What I’m trying to say is that every day I learn something new about St. Vincent, but I will never know him the way I know myself or even the way I know members of my family. My knowledge function approaches but never reaches the level of knowledge that I would like. That is frustrating.

I suppose that’s true of any work of history, but when just one person occupies so much real estate in your own mind for so long, the frustration of not knowing matters that much more.

I know a lot about my subject, of course, because I’ve read thousands of his letters and seven full-length biographies of him. But when you put in all that work and you still find gaps in his story, you want to do whatever it takes to fill them in.

That brings me to my recent archival hunting expeditions—or, it will, eventually. I’m going to take the scenic route.

Let’s talk about death

When we die, what do we leave behind? That’s a fundamental question for historians generally but for biographers specifically.2 I can think of at least four categories of our own legacies that matter to a biographer; I’m sure readers can think of more.

Memories of us in those who knew us (sometimes written down, sometimes not);

Our things;

Our correspondence;

Our bodies.

I’ll take them each in turn. My perspective, as I hope you gathered from the opening section, is that of a biographer searching for that little extra bit of knowledge that will bring me thismuch closer to knowing my subject, even while acknowledging that our knowledge of the dead (or even of other living people, for that matter) will always be imperfect and incomplete.

Memories of us in those who knew us matter enormously to biographers of the recently deceased—they can interview people who knew their subject. My subject died in 1823, but memory is still an important category of knowledge for me because two men who did know him wrote biographies of him in the twenty years after his death. Also, stories about him pop up in his family’s later correspondence, and his grand-niece was responsible for collecting and donating the largest portions of his correspondence that survive in the archives. How to treat this kind of personal knowledge is the subject of many books and much chin-scratching; I’m not going to focus on it in this post because I have a different agenda.

Our things tell us a lot about what we valued in life, and all biographers are naturally interested in their subject’s material possessions. In my case, his country estate burned down in the 1970s, long after his descendants had moved out. All I have besides his will are some descriptions of what the house was like. That’s useful, but I can’t sleep where he slept, the way (for example) an Austen biographer can:3

Obviously, then, what matters most to me for my biography is my subject’s correspondence. I don’t know how many letters he wrote and received in his life, but to take a wild guess, the lower bound probably approximates to the number of days he was alive: 32,193. Many are missing; the ones that exist were kept for reasons I need to understand. But I’ve read, or plan to read, as many as I can.4

Early in my research, I was excited to come across his signature. I felt like I was in his presence. He had touched that page; now I was touching that page. Since I cannot sit in his chair, like you can sit in Jane Austen’s chair, I had to forge a physical connection through less satisfying means.5 I know, of course, that touching the same paper does not actually help me understand the man, but as I said above, he occupies an enormous amount of intellectual real estate in my head. I was just happy to feel like I was making progress in getting to know him.

I think that explains why biographers also spend energy on the fourth legacy we leave behind: our bodies. I’ve previously told a story about coming across a part of St. Vincent’s body in the archives. That was certainly the most visceral experience I’ve had of trying to understand this man by being in his presence. I have not made it to his grave, which is in Staffordshire, but I expect I’ll want to go one day if only to be able to describe it to my readers.

The historian Erik Loomis takes this impetus to absurd lengths. He’s visited nearly 2,000 graves of various notable people and written short biographies of them. The series is amazing and awe-inspiring. He likes being in graveyards, which is part of his motivation, but he also puts his own body physically close to the people he’s writing about, even if all that’s left is some bones.

Horcruxes

Most of my early research on St. Vincent happened in four places: the Staffordshire Record Office, where his family was from; the National Archives at Kew, where most of his official naval letters are; the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, where he has several important volumes especially related to Nelson; and the British Library, where the bulk of his personal and family papers were deposited by his grand-niece. Since those were the four largest collections, I focused most of my energy there.

I still need to go back to some of them, but now I’m getting to the stage of the research process where I need to spend time on smaller collections scattered around the world.

That brings me, finally, to the purpose of this post.

I feel the need to honor Robert Caro’s call to “turn every page” in the archives. While highly impractical, I understand now why he made that promise. I admit that I can never truly know my subject, but so long as I have the means and the motivation, I don’t think I will be happy with the final product if I leave pages unturned. I will, I know, but my pride as a historian wants me to make the number of unturned pages as small as possible. The closest I can get to St. Vincent, and by far the best way for me to learn about him, is to read his letters.

Tracking them all down has made me feel a little like Harry, Ron, and Hermione in the last Harry Potter book. They (and Dumbledore before them) had to be Voldemort biographers to hunt for his horcruxes. Moreover, the horcruxes were pieces of Voldemort’s soul, and (if you’ll allow me to stretch this comparison to its breaking point) St. Vincent’s letters are as close as I can get to his.

Some of these letters, these pieces of him, are scattered around the world. I’ve identified fifteen other archives besides the four I already mentioned. The Huntington Library in San Marino, CA, has 31 letters, for example; there are another 59 at Duke and 4 at Harvard. Thankfully, St. Vincent’s horcruxes did not get created when he murdered people; rather, they are products of his letters being sent all around the British Empire and (in some cases) Gilded-Age Americans’ enthusiasm for buying British archival collections.6

Several of his letters are in places that I have known well. Just as Harry, Ron, and Hermione discover horcruxes in Hogwarts Castle, I’ve learned that I’ve been close to St. Vincent all this time. Little did I know when I visited my sister at the University of Michigan twenty years ago that it houses an essential collection of St. Vincent’s correspondence with the earl of Shelburne. I recently learned from letters at the British Library that when I lived in London, I lived just one block from where St. Vincent lived as a bachelor. Brown has several of his letters but also lots of caricatures of him, a collection that I would have almost certainly overlooked had I not moved to Rhode Island. He even shows up in the National Archives in DC, where I grew up, and at the Naval Academy, where I’ll be this week.

So my quest to turn every page is ironically bringing me back to places that I know well, but for an entirely new reason. I’m not making any pseudo-spiritual point here. I’m just struck by how my life has become intertwined with his life. My quest to know him perfectly will fail, but my goal is for it to fail as close to the line of truth as possible.

Please don’t think too hard about that graph. No, it doesn’t quite work, does it.

I’m speaking here about biographies of the dead; writing a biography of a living person presents entirely different challenges which I do not feel qualified to discuss.

Yes, JEANINE, I know you’re not allowed to sleep in her bed. The point is, it exists and you can look at it from up close.

Contemplating his correspondence has caused me to think about my own correspondence. How much will survive? Will anyone be able to read it when I’m dead? The 1990s are likely to be a challenging decade for historians, since so much of the material produced then ended up on now-decayed/unreadable floppy disks. When’s the last time you tried to get your computer to read a floppy disk? I doubt the cloud-based storage systems we rely on today will fare much better, but perhaps I’m being overly pessimistic.

Yes, JEANINE, I know you’re not allowed to sit in her chair. You’re the worst, Jeanine.

In any case, you never know what you might find in an archives, despite what the catalogue says, so I need to roll the dice and hope that I can answer some outstanding questions in some out-of-the-way places.

Great substack post. I’m sure you know, but the Huntington Library has “virtual reading room” appointments. They’re an hour long, and during that time, one of their archivists sits with a camera on a desk and displays each document you want to see. You can take a screenshot of them, or they will email you scans of up to ten pages. And it’s free! You can have as many as you want, just one hour at a time. It’s been a godsend to me as I’ve been researching my biography of Robert Anderson of Fort Sumter fame. https://researchguides.huntington.org/usingthelibrary/remoteservices#s-lg-box-33138567

Many thanks for this wonderful essay. It perfectly describes my own experience in preparing a book on LBJ’s war on poverty. I’m teetering on the edge of writing and doing yet more research because I want to get as close as possible to the “nature” of the subject.

Thanks also for the word “asymptotic.” It’s the best word possible for historical research! I’d never heard of it before last Monday …