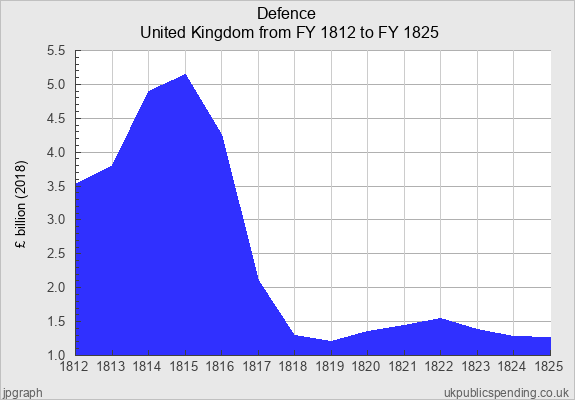

In his doctoral dissertation, Henry Kissinger claimed that Britain in 1815 was so powerful, it could “fashion a new interpretation of reality.”1 But last week, I showed you this chart:

Can you “fashion a new interpretation of reality” (by which I think he meant, reshape the global order) if you starve your army and your navy of funds?

It turns out that no, you can’t.

Kissinger is not alone in using “Britain in 1815” as a common shorthand for “a global superpower.” One of the contributions that I hope The Horrible Peace makes is to push back on that framing. This post looks at some examples of Britain’s inability to dominate the world stage in the decade after 1815 and why I think that matters today. For lots more like this, buy the book. You can also support my work by sharing this post and subscribing, if you haven’t already:

Pirates in the Caribbean

The end of the Napoleonic Wars did not mean world peace had arrived, especially in the western hemisphere. In South America, Spanish and Portuguese colonies were in open rebellion, and guns no longer needed in Europe flowed across the Atlantic. Partly as a result of those rebellions, and partly because of the presence of so many demobilized sailors in the region, piracy erupted in the Caribbean, just as it had in the “Golden Age” a hundred years earlier.2 Some of the pirates were actually privateers commissioned by the fledgling republics; others were commissioned by Spain, whose navy was in shambles; and still others were true pirates, like the famous Lafitte brothers, who operated without the official support of any state. A good example of the complex, interlocking forces at play was the privateer Ant, which claimed to operate out of Buenos Aires in support of Argentinian independence, but had actually been fitted out in Baltimore. In the power vacuum created by the end of the global war and the withdrawal of naval forces, opportunistic shipowners preyed on lightly-armed merchant ships throughout the Americas.

Sounds like a job for the Royal Navy, right? After all, if Britain in 1815 was like the US after 1991—a global superpower policing the world’s seas—we might expect the 1815 equivalent of this scene to have happened:

But instead of the 1815 equivalent of today’s US Navy showing up, the actual US Navy showed up. Let me explain.

British merchants, caught in the crossfire of the South American wars, suffered serious losses, especially in 1817 and 1818, and they demanded that the Admiralty do something to protect them. But the navy simply didn’t have the capacity to deploy large numbers of ships to the region or to organize convoys that would have provided the best protection. Instead, the first navy to deploy a dedicated anti-piracy squadron to the region was the US Navy, which naturally caused British merchants to complain that the US Navy was doing the Royal Navy’s job for it.

The world’s first arms limitation agreement

Slashing and burning the budgets of the military that had won Britain its great victory meant that ministers no longer had that military as a foreign policy tool. The navy, dependent as it was on expensive ships to function, had a particularly tough time. In the years around 1815, tired ships returned to the dockyards to be refitted, broken up, or stored for future use. But with no funds for the dockyards, not to mention no funds to pay the sailors on the ships, the navy’s readiness collapsed. In 1813, at the height of the wars, there had been well over 100 ships of the line (what they called battleships in the age of sail) in service or in reserve if needed. By 1818, there were just 37 in good enough shape to be deployed, and fewer than 20 actually in service.

So it's not surprising that when British merchants in the Caribbean whistled for help, the wrong navy showed up. But it was also potentially a serious problem that it was the US Navy, of all navies, that did. The Caribbean was one of many arenas where American and British forces met each other in the postwar decade, and the chance that they would go to war again was high. That's because the War of 1812 had resolved nothing—literally. The treaty that ended it in February 1815 reset relations to what they had been before the war, so there were plenty of people on both sides who thought there were still reasons to fight. In the Caribbean, American and British interests tended to align, but elsewhere, they did not. In Florida in 1818, Andrew Jackson executed two British citizens. He accused them, with dubious evidence, of spying for the Seminoles, whom he was trying to exterminate. In Oregon, American and British imperial projects proved tricky to untangle. On the Great Lakes, site of some of the most intense fighting in the war, both sides began ambitious shipbuilding programs. War seemed likelier than not.

Instead, though, both sides backed down. The US realized that the public's enthusiasm for shipbuilding might not last as long as the navy hoped, and Britain was looking for every possible way to save money to deal with its debt. The result was the Rush-Bagot Pact of 1817, the world’s first arms limitation agreement. Both sides agreed to stop the shipbuilding race on the Great Lakes, and the next year, they settled part of what became the US-Canadian border.

Restraint or weakness?

As these brief glimpses into British foreign policy in the postwar decade show, Britain was not a colossus bestride the world, dictating its terms to all challengers. Instead, it was broke, trying desperately to avoid another war. If that meant ignoring Andrew Jackson’s provocations, fine. If that meant letting the US Navy shoulder some of the trade protection burden in the Caribbean, fine. The point is, for about a decade after Waterloo, Britain did not act like a global superpower because it did not have the capacity to do so.

I am not arguing that Britain was weak throughout the nineteenth century, or that the Pax Britannica never happened. The postwar budget and readiness crisis for the two services lasted about ten years. In 1824, the army began a serious recruitment drive in the British Isles, freeing up forces to be deployed into the Empire. That same year, the navy used steam vessels in combat for the first time: first in Algiers, and then later that year in Burma during the First Anglo-Burmese War.3 Note how far apart those two places are. At that point, with true global power projection becoming a reality, talk of a Pax Britannica begins to make more sense.

One obvious criticism of all this is to say, well, who cares what historians write about Britain in 1815? What’s the harm in saying that the country that dominated the rest of the nineteenth century was a superpower in 1815? Well, history informs policy. The influential Princeton political scientist John Ikenberry has long argued that the US should pursue a policy of “strategic restraint.” The US, in his view, should place limits on its own power to secure a legitimate and institutionally-based global order. This isn’t the space to discuss the merits of that as a policy recommendation, but I think it’s important to point out that Ikenberry based his theory in part on British policy after 1815, which he depicts as exemplifying “strategic restraint.” I think that’s wrong. Britain acted with caution after 1815 because it had no other choice.

And of course that brings us back to Kissinger, whose influence on American policy continues to be felt even as he approaches his 100th birthday on May 27.4 I’m not sure any country has ever been capable of fashioning a new interpretation of reality, but for the decade after 1815, Britain certainly wasn’t.

I was under the impression you needed drugs for that.

That’s when Pirates of the Caribbean takes place.

This conflict has largely been forgotten in the West, but it shouldn’t be. Recent nationalist military regimes in Burma have used 1824 as the cutoff date for determining Burmese borders, and therefore who belongs in Burma today and who does not.

For the latest news: https://twitter.com/DidKissingerD1e.