Welcome new readers! As a reminder, this series is about re-reading Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey-Maturin novels, and in these last few posts, we’ve been concentrating on Post Captain. Since that novel is the most Austenian of O’Brian’s novels, I’ve used it as a starting point to talk about Jane Austen and the navy. Don’t worry, though, Aubrey makes an appearance, and he and Maturin will make even more appearances in future posts.

The subject of this post is common, in the sense that you can find lots of information about Jane Austen’s two naval brothers on the internet. The Wikipedia pages for Francis Austen and Charles Austen are extensive, and there’s a good blog post from the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich that covers both their careers and Austen’s naval characters.

My challenge, therefore, is to add some value.

The Brothers

Let’s start with some character sketches, just so we’re all on the same page:

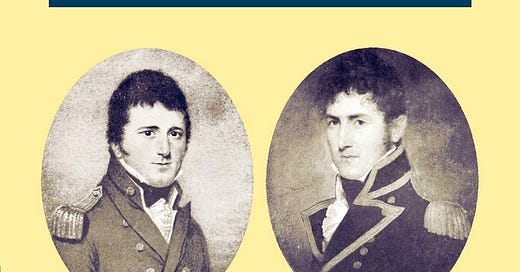

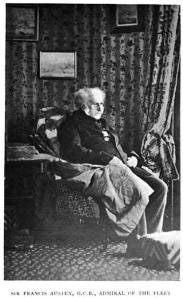

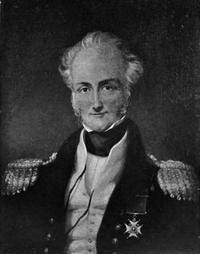

Sir Francis William Austen (1774 – 1865) joined the navy in 1786 and died as Admiral of the Fleet, the highest rank in the navy. Along the way, he saw lots of action, especially while in command of HMS Peterel, a 16-gun sloop roughly similar to Aubrey’s Sophie. In fact, the similarities between Austen’s career and Aubrey’s are striking. Both men captured lots of prizes at the end of the French Revolutionary Wars (1792–1801) and both men eventually leveraged their success in small-ship actions into promotion to post captain. Both men also missed Nelson’s great victory at Trafalgar—in Austen’s case, he was part of Nelson’s squadron and should have been there, but Nelson had to detach him to convoy supplies to Gibraltar just before the battle. Austen regretted that for the rest of his life, but the next year, he participated in the last fleet action of the Napoleonic Wars, the Battle of San Domingo.1 He remained in active service through the War of 1812, after which he probably expected to be on the beach for the rest of his life. Surprisingly, in 1844, aged 70, he became commander-in-chief of the North America Station, responsible for managing British interests during the Mexican-American War. When he hauled down his flag at the end of that command, his active career ended.

His younger brother Charles Austen (1779–1852) joined the navy in 1791 and also saw service throughout the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. He made post in 1810, and unlike his brother, saw a good deal of active service in the years after 1815 in the service of the British Empire. He went to Jamaica in 1826 as part of the anti-slave trade patrol, he fought the Ottomans in 1840, and he died of cholera while commanding forces in the Second Anglo-Burmese War.

Career Assessments

The first and most important thing to understand about Francis is that his rank is not important. Being Admiral of the Fleet was a great honor to all outward appearances, but everyone who understood the navy knew that it just meant he was very old. After all, once you promoted from commander to post captain, promotion thereafter proceeded by seniority. So, the earlier you were a post captain, the earlier you were a rear admiral, the earlier you were a vice admiral, the earlier you were an admiral, etc. Austen had the good fortune to be promoted to post captain aged 26 and the even better fortune to live to be 91. Plenty of officers were promoted to post captain at younger ages (Nelson was 20, for example), but 26 was respectable.

As a naval historian who has written a lot about men like the Austens, when I read their career summaries, I can tell they were competent. They regularly got employment and opportunities to demonstrate their skills. In the language of the time, both men were “active and enterprising.” They knew their profession; they were brave; they performed well when given the chance. In more than two decades of great-power wars, there were lots of chances.

What I find unusual about the two men (aside from their world famous sister) is how they joined the navy—the Portsmouth Royal Naval Academy. Obviously a shore-based academy is a normal route into the navy today, but it was unusual in the eighteenth century. In a database I built for my first book, just two percent of officers entered the navy that way from 1775 to 1805. Most aspiring officers joined a ship in commission, which required just the consent of the ship’s captain—in the O’Brian universe, think of young Babbington. The Austens probably ended up at the Academy because their father, a country parson, had no strong naval connections. Also, his boys joined the navy in peacetime, when there were fewer captains at sea. Moreover, the Academy promised to give his boys a well-rounded education, with classes in French, mathematics, fencing, dancing, and drawing. You had to know some Latin to get in—another plus from the perspective of a churchman, no doubt.

In practice, however, the Academy never fulfilled its potential. It turns out that letting 40 teenage boys loose in a port town creates all sorts of trouble. Admiral John Jervis, earl of St. Vincent, described the Academy as “a sink of vice and abomination that should be abolished.” One student remembered being beaten by the schoolmaster, playing pranks on a local farmer, and raiding what he called a local “gipsy” encampment. The Academy was also expensive compared to sending a boy to sea. Most of the boys at the Academy did not come from naval families—those in the know avoided it. The Austens weren’t in the know, but they made successful careers anyways, which is yet more evidence that they were skilled officers.

Jane and Her Brothers

Jane wrote to her brother Charles in December 1798:

I have got some pleasant news for you which I am eager to communicate, and therefore begin my letter sooner, though I shall not send it sooner than usual. Admiral Gambier, in reply to my father’s application, writes as follows: ‘As it is usual to keep young officers [Charles was then only nineteen] in small vessels, it being most proper on account of their inexperience, and it being also a situation where they are more in the way of learning their duty, your son has been continued in the Scorpion; but I have mentioned to the Board of Admiralty his wish to be in a frigate, and when a proper opportunity offers, and it is judged that he has taken his turn in a small ship, I hope he will be removed. With regard to your son now in the London [Francis], I am glad I can give you the assurance that his promotion is likely to take place very soon, as Lord Spencer [the First Lord of the Admiralty] has been so good as to say he would include him in an arrangement that he proposes making in a short time relative to some promotions in that quarter.’2

Sure enough, Francis was soon promoted to command Peterel and Charles moved into a frigate, HMS Tamar. Gambier, one of the members of the Board of Admiralty, was the key patron for both men. They were distantly related: Gambier was married to a first cousin of Jane’s eldest brother’s first wife. However, it does not appear that Gambier helped either Francis or Charles until they had been in the navy for a few years.

As a historian, here’s what I notice about Jane’s letter:

It’s an example of how women transmitted knowledge and maintained patronage networks;

Being a talented officer provided opportunities to leverage distant connections to attract powerful patrons;

All successful careers required connections, initiative, and luck, in some combination.

Gambier is an interesting figure in his own right—he was one of the founders of Kenyon College and namesake of Gambier, OH—but that’s enough for today. We’ve left Jack and Stephen a little too far behind; we’ll return to them next week.

That’s the same battle that his sister’s character Captain Wentworth participates in before he meets Anne Elliot in Persuasion.

John H. Hubback and Edith C. Hubback, Jane Austen’s Sailor Brothers: Being the Adventures of Sir Francis Austen, Admiral of the Fleet and Rear-Admiral Charles Austen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1906), 48–53.

Great discussion, we just finished watching on PBS here the latest Miss Austen series based on the writings of Gil Hornby which led us to the Wikipedia articles on these brothers. Thanks for the added insights. I’ve put several titles on my To Read list and tagged to follow you on Goodreads (though they haven’t a clean profile there and appear to have two or more similarly named authors together as one).