Nelson's Left Hand

Necessity is the mother of learning

Travel has caught up to us, and we don’t have a post for you on Patrick O’Brian this week. Similar to the post a few weeks ago about whether everyone was always drunk in the eighteenth-century navy, here’s a short post with a few documents I found in the archives. I don’t have anything original to say about them, but sometimes it’s fun just to get to touch history.

For new readers, I’ve also included some links to past posts, set off in italics, that you might find interesting.

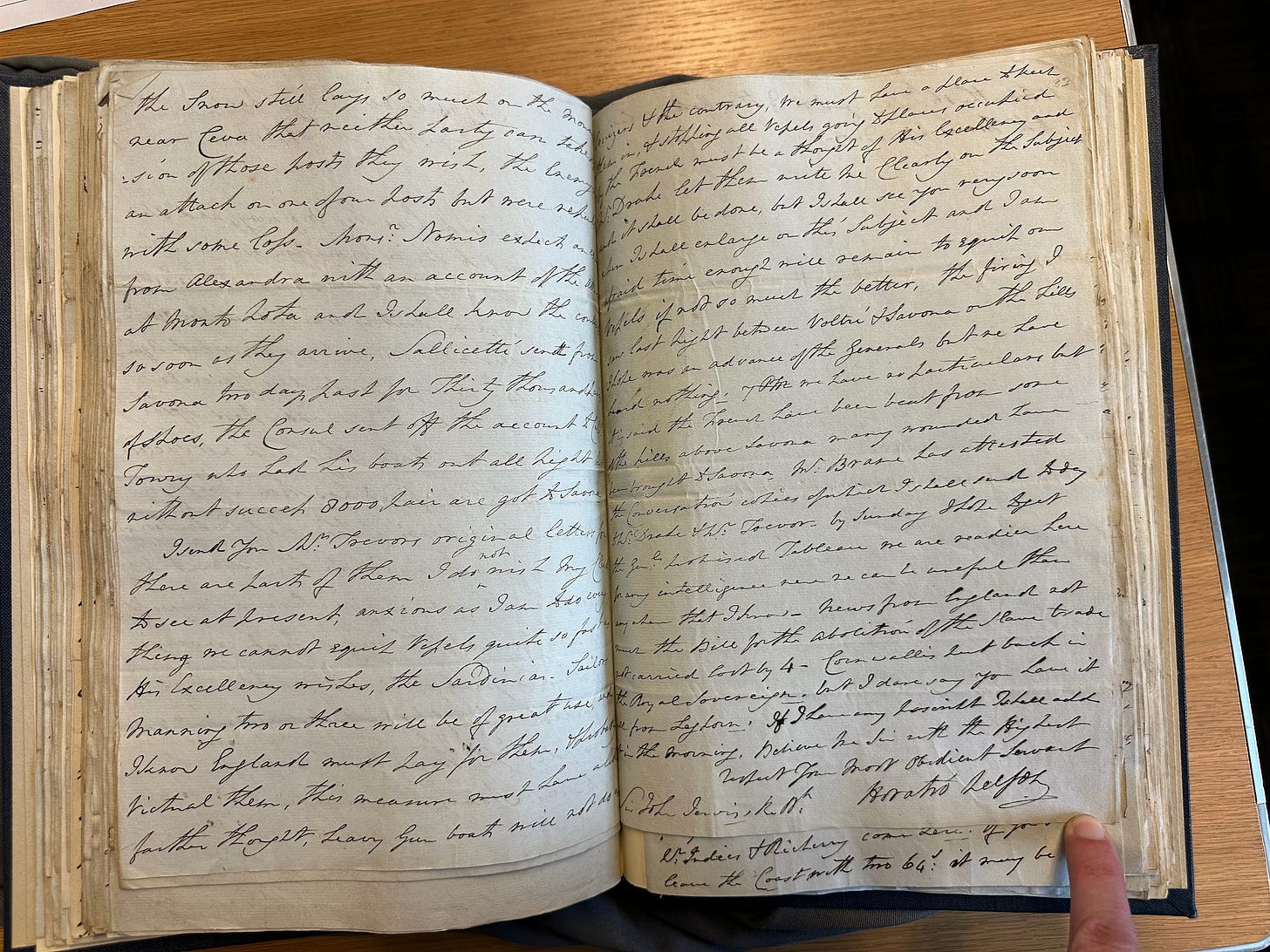

First up is a letter I read the other day from Captain Horatio Nelson to Admiral Sir John Jervis, Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet. The content of the letter (dated April 15, 1796) isn’t really that interesting. Just focus on the handwriting:

Nelson had pretty good handwriting. Importantly, though, he was right-handed. And in July 1797, Nelson lost his right arm in the assault on Santa Cruz de Tenerife.

The point of the assault was as much to keep the fleet busy in the aftermath of the Great Mutinies as it was to capture another set of Spanish treasure ships. Here are three recent posts on those subjects, in case you missed them:

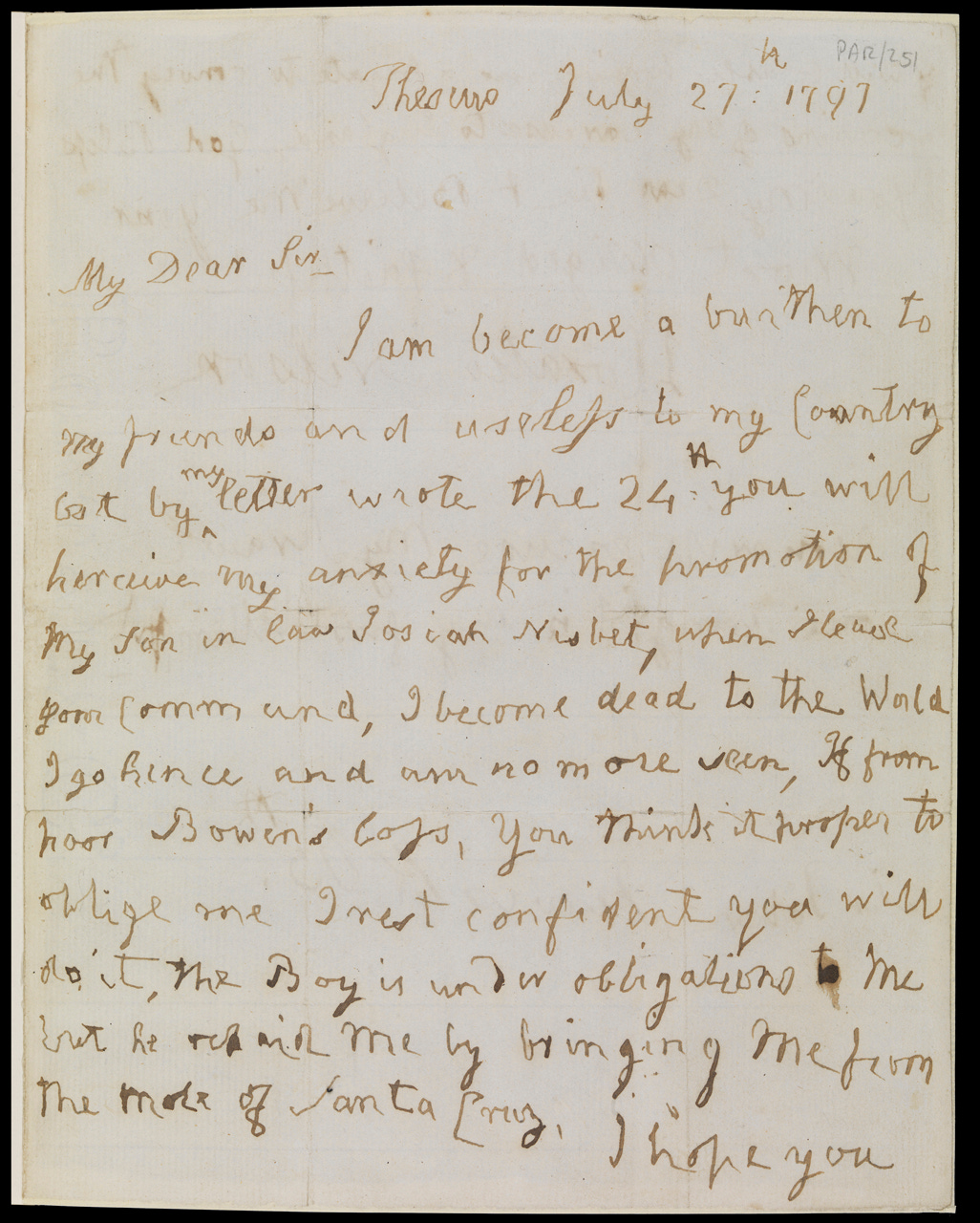

Nelson was lucky to escape with his life. The National Maritime Museum has the first letter he wrote with his left hand. His morale was very low, and his handwriting was understandably terrible:

The first line reads, “I am become a burden to my friends and useless to my Country.”

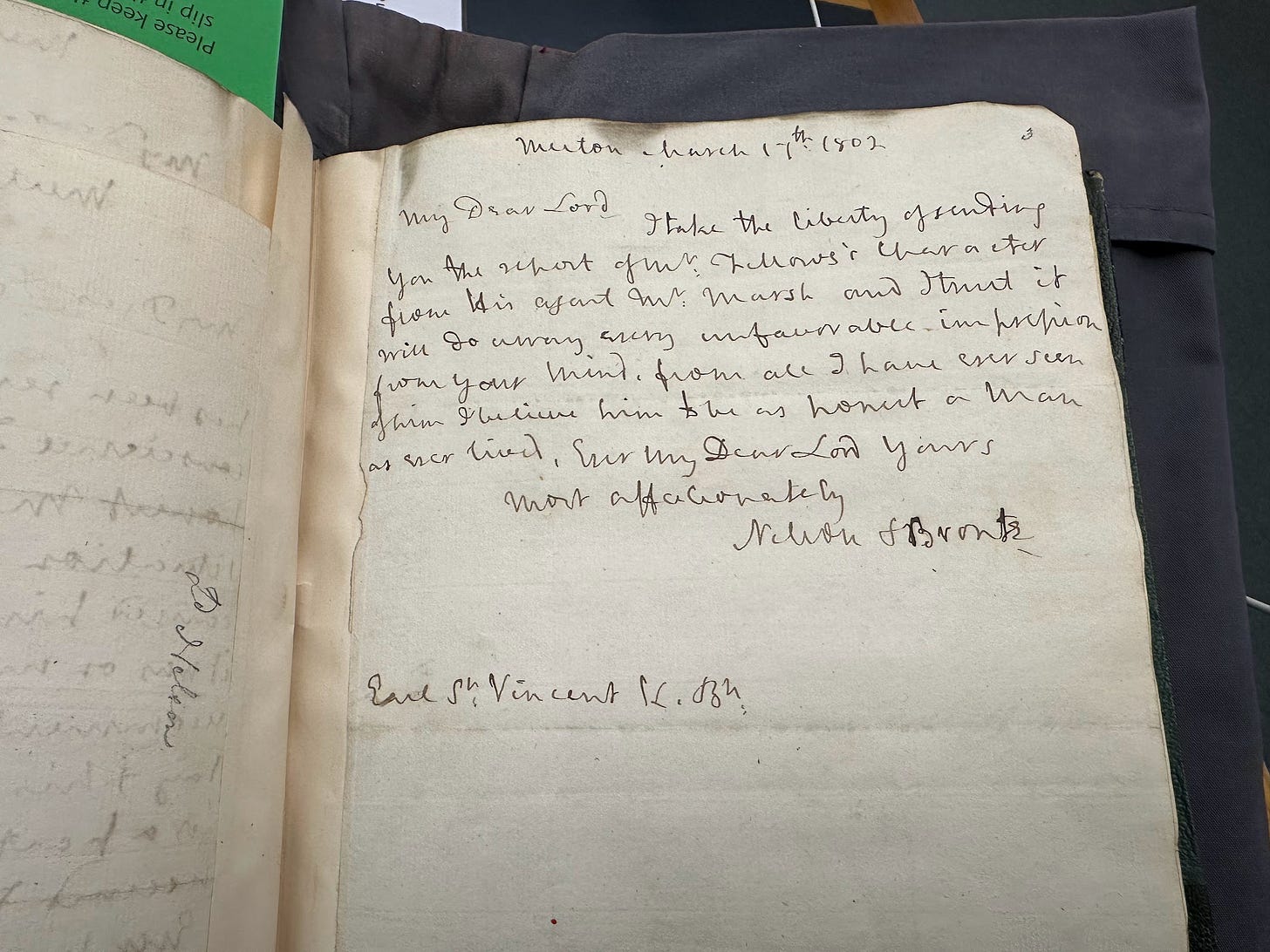

But check out how much better his morale and his handwriting were five years later. Here’s Nelson writing to Jervis again, this time in 1802. Both have moved up in the world:

Nelson’s left hand still takes some getting used to, but it’s much more regular than in his first letter. He signed it “Nelson & Bronte” because King Ferdinand IV of Naples created him the first Duke of Bronte in 1799 to thank him for his (highly suspect) service to Naples in the aftermath of the Battle of the Nile. Meanwhile, Nelson’s key contribution to the Battle of Cape St. Vincent helped Jervis become the first Earl of St. Vincent.

Reading and touching Nelson letters provides a small thrill, I admit, but many of them are missing their signatures. Autograph hunters have smuggled exacto knives into archives to cut out signatures of famous people. Please never buy a signature by itself on eBay! Nobody signs slips of paper; the obvious conclusion from a signature by itself is that it used to be in an archives and part of a letter.

I still remember when I found James Monroe’s signature in the British National Archives. A U.S. President! Wow! I was a first-year graduate student and I emailed all my historian friends. They laughed and told me to calm down. They’re right: the small thrill of a famous signature fades over time. But if you can’t get at least a little excited about this sort of thing, then I think you’re in the wrong business.

Long-time readers will remember an even more intimate archival encounter:

Back to Patrick O’Brian next week, I hope.